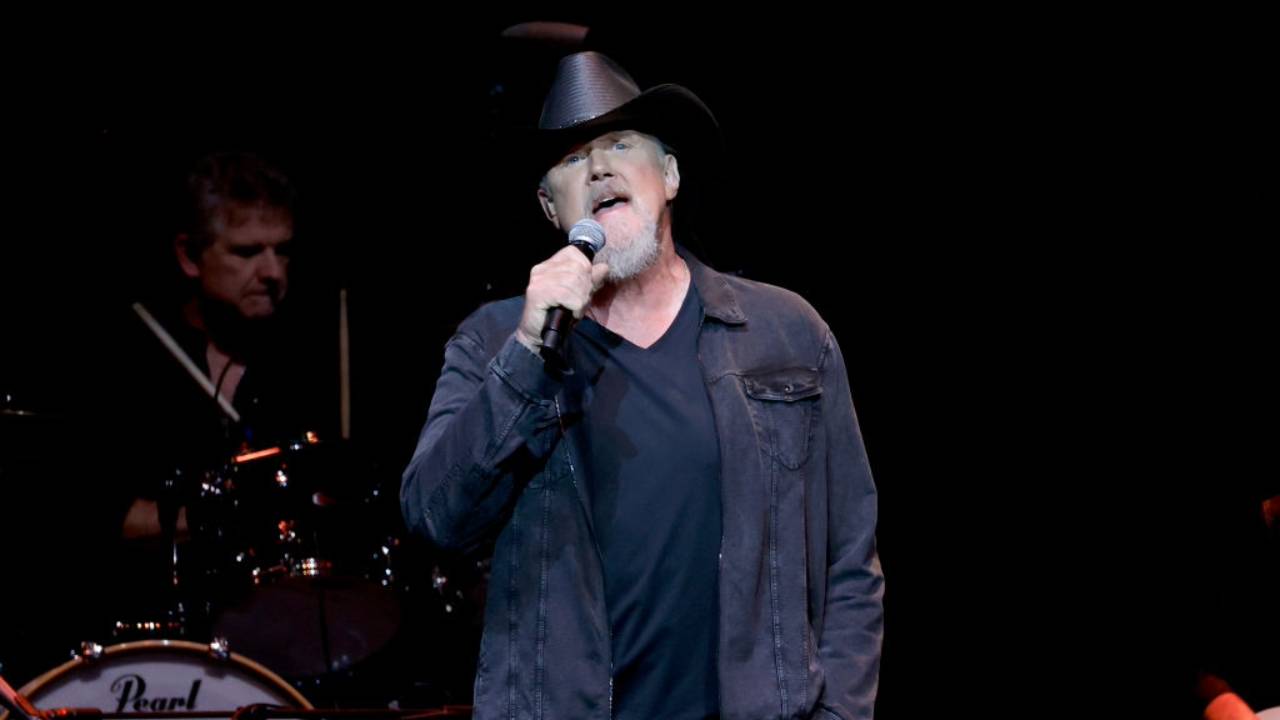

Steve Azar Never Far From the Delta

A native of the Mississippi Delta, Steve Azar comes by his blues-inflected country sound naturally. His father opened the state’s first legal liquor store in 1964 in his hometown of Greenville, Miss. The business sat about a block from the famed crossroads of Highway 82 and Highway 1. Eight miles east was Highway 61.

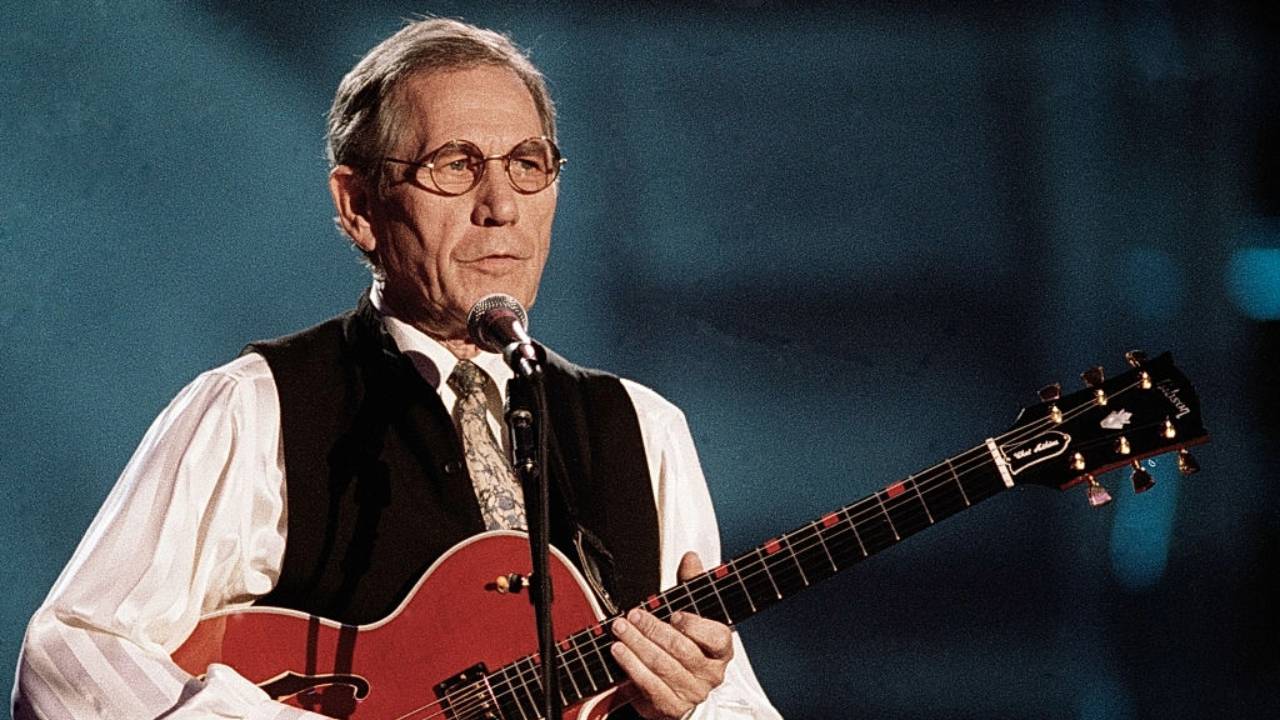

This region produced country star Conway Twitty, as well as dozens of blues legends. In fact, one of these Delta bluesmen, Eugene Powell (a.k.a. Sonny Boy Nelson), used to hang out at the store with a guitar, a bottle of Wild Irish Rose and a litany of wonderfully profane songs. This was where a 10-year-old Azar, now famous for the hit “I Don’t Have to Be Me (’Til Monday),” learned to play guitar. Even at a young age, something about that heartfelt music resonated in him.

“They just didn’t lie. They told the truth about everything. They were very mysterious, and so were their songs and their style of playing,” says Azar, now 38. “Country music to me has always been about real life and real things and real people and real life situations, a lot like the blues was. I’m not a blues man, I didn’t live their life. I grew up around it. I used to sneak into blues bars and play, the only white boy in there. I was always grounded growing up.

“I’ve definitely been heavily influenced by it, but my biggest influence was the land I grew up on, and the Mississippi River,” he continues. “I write and talk a lot about where I’m from and that’s the big influence for me. People keep asking, ‘You gonna do a blues record?’ And I keep saying, ‘Well, I could mentally, because I’ve been beat up since I’ve been in Nashville.’ But a blues guy’s gotta be a blues guy, gotta be the real thing.”

Before moving to Nashville in 1993, Azar actively toured the Southern circuit -– “playing anywhere from a biker bar to fraternity and sorority parties to a silhouette dance to a ninth grade dance,” he says. “We played everywhere, any place that would have us. A lot of country bars and a lot of rock bars, and anywhere in between.”

He ultimately signed with independent country label River North, which folded shortly after Azar’s first single. In time, one band member committed suicide, while another murdered his own girlfriend. With a crushed spirit, Azar decided to perform acoustic shows, despite the fact that two truckloads of band gear still weren’t paid for. When he finally assembled some friends for a new band, he found they didn’t sound as good as his previous lineup.

In other words, the enthusiastic escapism of “I Don’t Have to Be Me (’Til Monday)” is hard-earned and real. The accompanying video plays up the fun-loving side of the song, although it was not initially what Azar had in mind.

“I had this big struggle [with the video’s director and producer, who said], ‘We want to do this really flashy,’ and I’m going ‘No no, I just can’t handle flash. I want it to be earthy, like where I grew up.’… That boat I’m sitting on in the middle reminds me of the Delta. It’s really rustic and rusty. I haven’t been around anything really shiny and perfect in my life, so to me, real life represents scars and scrapes and bruises and rust.”

Azar wrote or co-wrote every song on the album Waiting on Joe. He relied on his brother Joe’s typical tardiness to inspire the title track, although the song, in which a car/train collision claims his friend’s life, eventually revealed more about Azar’s family than he expected.

“Greenville was a really hard-working town, so work was always on my mind. And waiting. Everybody down there is waiting on something. I’ve been waiting on this, you know? That waiting to me was a lot more than waiting on a person,” Azar explains. “Also, the train represents the thing that comes along to spoil your dream or, forget dreams, spoil all the hard work you’ve been doing.

“But also, I had an uncle named Joe, my mom’s little brother, who was my godfather, who was mayor of Clarksdale, Miss., who died of cancer at 35,” Azar continues. “I was 9 or 10 years old when it happened. I think my grandmother, at times, is still waiting on my uncle to come back. And I see my mom. They have never gotten over that. And now looking back, I can see why. He was my grandmother’s child; he was a little boy, a baby boy who was a cancer victim. He had so much potential. You know, you can’t help but notice all of these things while you’re growing up.

“That song’s really my biography. To tell you the truth, I recorded it and put it in a drawer, I didn’t want anybody to hear it. My brother Joe got it out and sent it to [the record label]. I just thought that it was my personal thing. I have a whole lot easier time writing about other people than I do about myself.”

Nevertheless, listening to Azar’s album –- packed with slide guitar and produced by accomplished songwriter Rafe Van Hoy (“Golden Ring,” “What’s Forever For”) -- is like taking a backroads trip to the Delta region, with plenty of detours along the way.

“This has been a big journey for me, but I wouldn’t trade it for anything,” Azar says in his slightly raspy, rapid-fire dialect. "A year ago, I would have told you I hate this journey, this journey’s killing me, because I wasn’t getting to play. I wasn’t getting to do this. Trust me, it’s not a pride thing with me. If it was a pride thing, I’d have walked away a long time ago. It’s more about I love doing it, and this is what I’m going to do.”