NASHVILLE SKYLINE: Live on DVD: Heartworn Music

(NASHVILLE SKYLINE is a column by CMT/CMT.com Editorial Director Chet Flippo.)

Heartworn Highways posits an absolute truism: the best music and the best whiskey come from the same part of the country. That’s only partially true, since most of the music in this fabled documentary DVD is centered around Austin and Nashville and the best American whiskey -- sour mash and bourbon, that is -- comes from Kentucky and Tennessee. But the best music has come from around Austin and Tennessee.

The best summation of this music documentary was written 22 years ago by the film critic Pauline Kael in the New Yorker when the movie was released in theaters. “Watching it,” wrote Kael, “is like being carted off to a good party by people who told you where they were taking you so casually that the names of the people who were going to be there didn't sink in. You don't know how you got there or who the hosts are, and you never quite catch the last names of the assorted celebrities telling tall tales and singing lovely sad songs.”

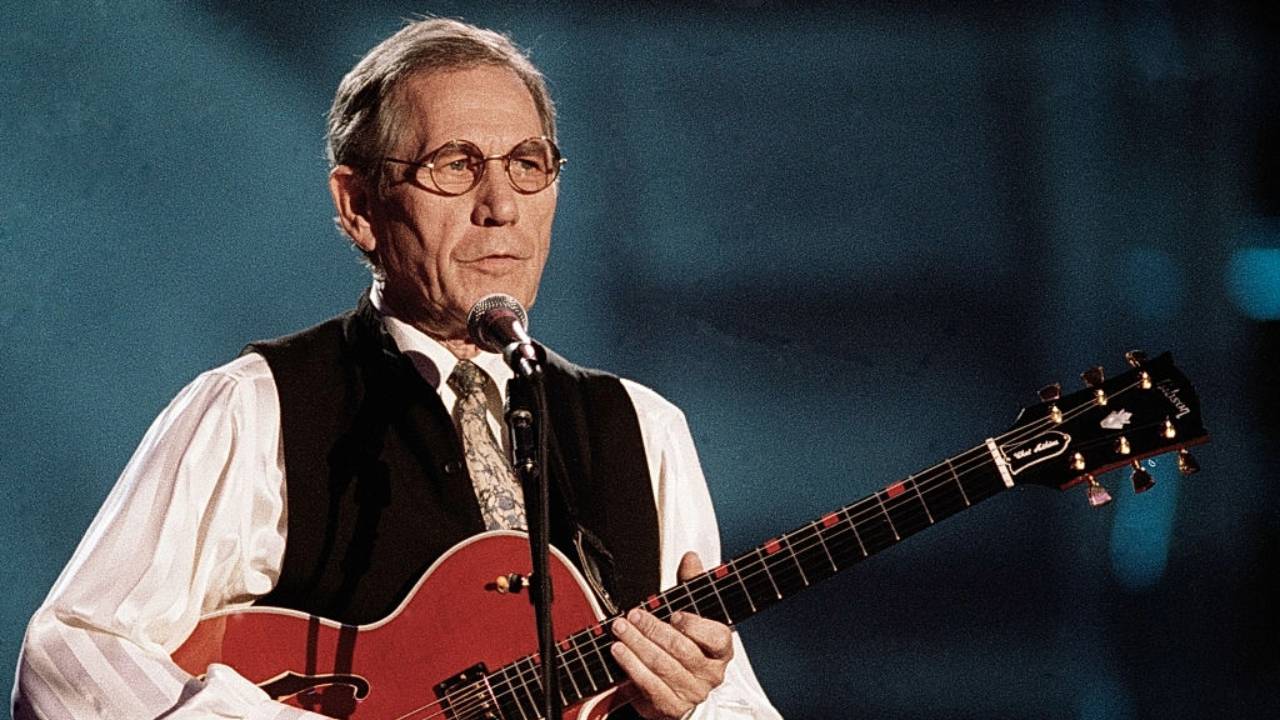

In this case, the celebrities singing the lovely sad songs are artists who were emerging in the Nashville and Austin music scenes in the mid-1970s when those scenes were changing radically. A casual viewer would need subtitles to know that the boyish Guy Clark, Rodney Crowell and Townes Van Zandt were becoming songwriting giants.

The 1975 Christmas Eve feast at the Nashville home of Guy and Susanna Clark is an overwhelming reminder of the close-knit sense of community that so many of the Austin and Nashville singer-songwriters formed. Sitting around a huge table weighed down by many bottles of wine and bourbon, the group finishes off the festive evening with a group sing of a raucous, but still reverent, version of “Silent Night.”

The documentary is somewhat scattered, but the performances are so frank and the glimpses of real life are so down-home and unaffected that they make the whole current concept of “reality TV” seem empty and invalid.

Some of the best moments from Heartworn Highways are from the scenes outside the music. Not surprisingly, what goes on around the music is in many ways more interesting and more revealing about the artist. The glimpses of the Jack Daniel’s assembly line at the distillery in Lynchburg, Tenn., accompanying Gamble Rogers’ song, “Black Label Blues,” are far more interesting than the song itself. And we learn more about David Allan Coe from his conversations with inmates at the Tennessee State Prison than we do from his music. Scenes of Van Zandt clowning around in the back yard -- clutching a can of coke, a fifth of Seagram’s V.O. and a B.B. rifle -- and talking with an elderly black friend open up a wealth of insight into Van Zandt’s personality and character. And, with the wisdom of hindsight, it’s easy to spot the aura of doom that had already attached itself to him.

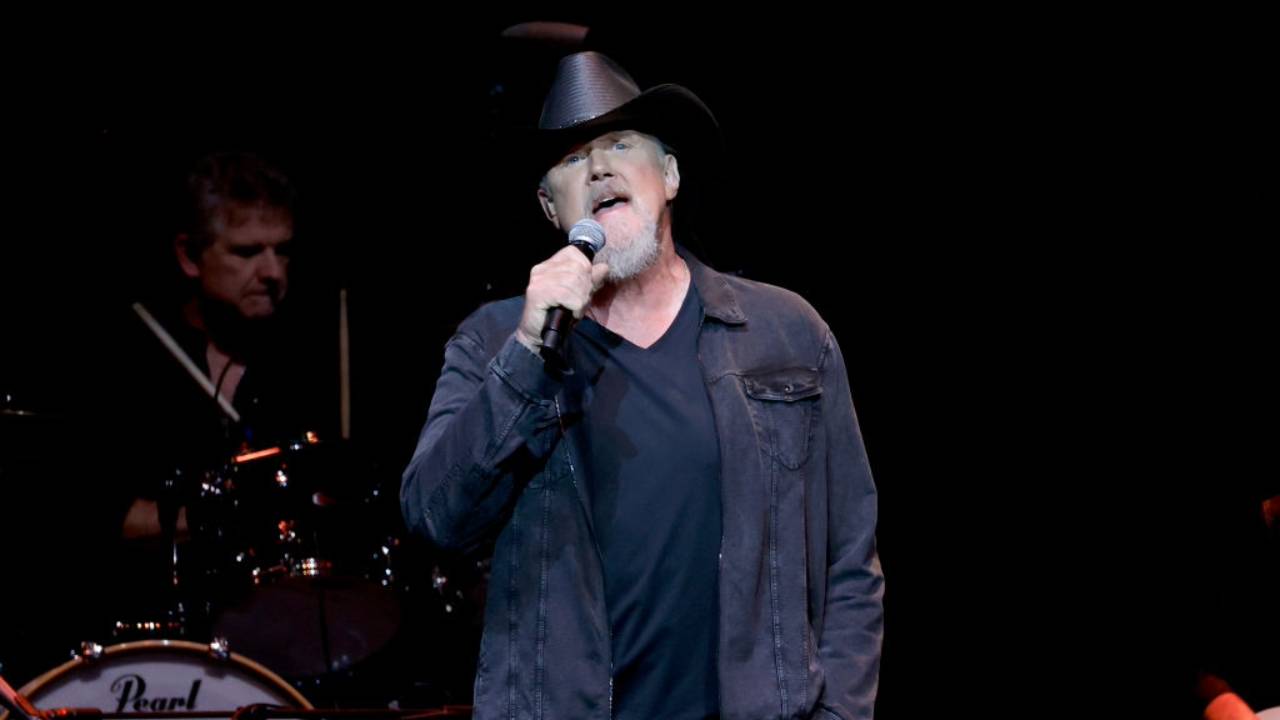

This is a disparate cast of characters here: Charlie Daniels, Barefoot Jerry, Larry Jon Wilson, Richard Dobson, Peggy Brooks, David Allan Coe, Glenn Stagner, John Hiatt, Steve Earle. Many of the songwriters became prominent. Steve Young wrote “Seven Bridges Road” and Waylon’s great “Lonesome, On’ry and Mean.” Crowell -- besides having a great solo career -- wrote “'Til I Gain Control Again” for Willie Nelson and “Ain’t Livin’ Long Like This” for Waylon. Coe penned “Take This Job and Shove It” for Johnny Paycheck and “Would You Lay With Me in a Field of Stone” for Tanya Tucker. Van Zandt wrote “Pancho and Lefty,” a great hit for Nelson and Merle Haggard, and “If I Needed You,” a hit for Emmylou Harris and Don Williams. Earle and Daniels carved out unique careers for themselves.

There is no storyline or any other sense of connectivity here. But the overwhelming continuity that emerges from this documentary is that of context: here’s a generation of fledgling artists who are trying out their wings in an unknown world. Some are awkward ugly ducklings, but all have something to offer.

The beauty is in the music. I counted 18 songs in the movie proper and another dozen in the “extras” section added to this DVD version of the movie. Especially valuable are several previously unreleased versions of several songs, including “Waitin' Around to Die” and “Pancho and Lefty” by Van Zandt, “Desperadoes Waiting for a Train” and “L.A. Freeway” by Clark, “Mercenary Song” by Earle and an intense, acoustic performance of “One for the One” by a young John Hiatt -- with much hair!

The preservation of those performances alone is a great gift to history. And they cause wonder about how many performances just as valuable as these have been lost to history. They demonstrate the impact that one person armed with an idea and a movie camera can have. The late Heartworn Highways director James Szalapski deserves our appreciation for what he accomplished.