NASHVILLE SKYLINE: New Documentary Captures Janis, the Band and the Dead at Their Peak

(NASHVILLE SKYLINE is a column by CMT/CMT.com Editorial Director Chet Flippo.)

One of the fascinations of watching the movie Festival Express at this week's Nashville Film Festival was being graphically reminded of the pitched battles that were waged more than three decades ago. These were fierce struggles -- that got down to hand-to-hand combat with the police -- over the issue of so-called "free" music. This, of course, was long before computers and the whole notion of downloading music for free. The only ways you could "free" the music back then was by shoplifting records or bootlegging live shows or by gate-crashing concerts.

The matter of "free" music in this case was a radical theory that began materializing around the giant live music festivals that blossomed in the late 1960s and early 1970s. The fans who declared themselves radicalized as members of the "counterculture" decided that music "belonged to the people" and should be free to all. So, gate-crashing became the accepted downloading mode of the time. Promoters and artists and cities and police departments didn't agree, so conflict was inevitable.

Festival Express itself stemmed from a very loopy idea. In 1970, some Canadian promoters got the notion to put a big festival on a cross-country train. How cool that would be: Put it on a train and take it across Canada where the artists would get off in cities and play festivals. This ended up being the last of the mammoth rock festivals that began with Monterey Pop and wound through Woodstock. The talent lineup was pretty impressive for the times: the Band, the Grateful Dead, Janis Joplin, Buddy Guy, Delaney & Bonnie & Friends, Leslie West and Mountain and almost two dozen more.

They ended up having endless backstage (on the train) parties and jam sessions that were occasionally interrupted by getting off the train and playing festivals for fans. At one point the train actually ran out of liquor and stopped at a liquor store next to a train station.

This footage had been locked up in legal proceedings for more than 30 years. What's noteworthy about it now is the lasting quality of much of the music, as well as the gritty depiction of life on the train and the battles between gate-crashers and police. As a music documentary, this serves up offstage footage you seldom saw in those days and will likely never see again in this era of sanitized coverage of the stars and superstars.

It's like being in a time warp seeing otherwise normal looking young hippies shouting, "Off the pigs," and charging and attacking police officers. The mayor of Calgary actually showed up at the festival and demanded that "the children of Calgary be allowed to freely walk through these gates." Concert promoter Ken Walker says in the movie that his conversation with the mayor ended with a dialogue between "my fist and his teeth."

In replying to the issue of gate-crashing, Bob Weir of the Dead, says, "This is how we make a living, man. Fifteen bands for 14 bucks -- what's so wrong with that?" In fact the ticket price was $14 for a two-day music festival with over 20 musical acts.

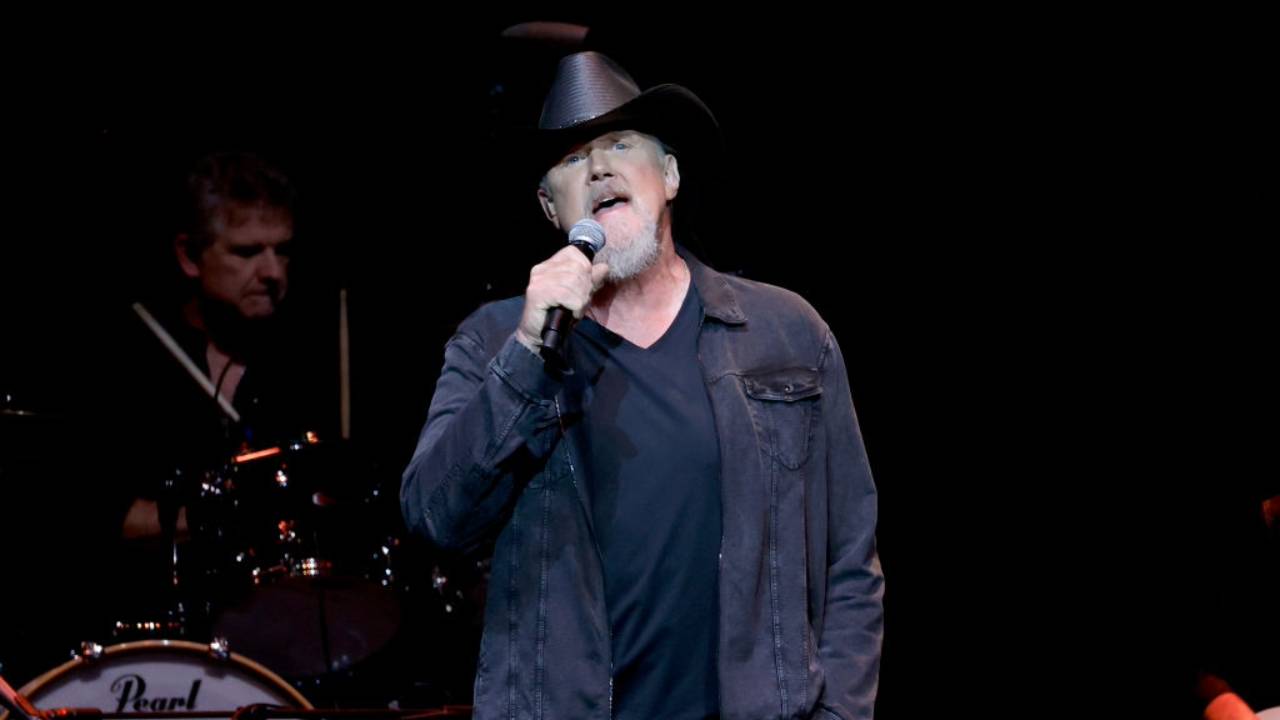

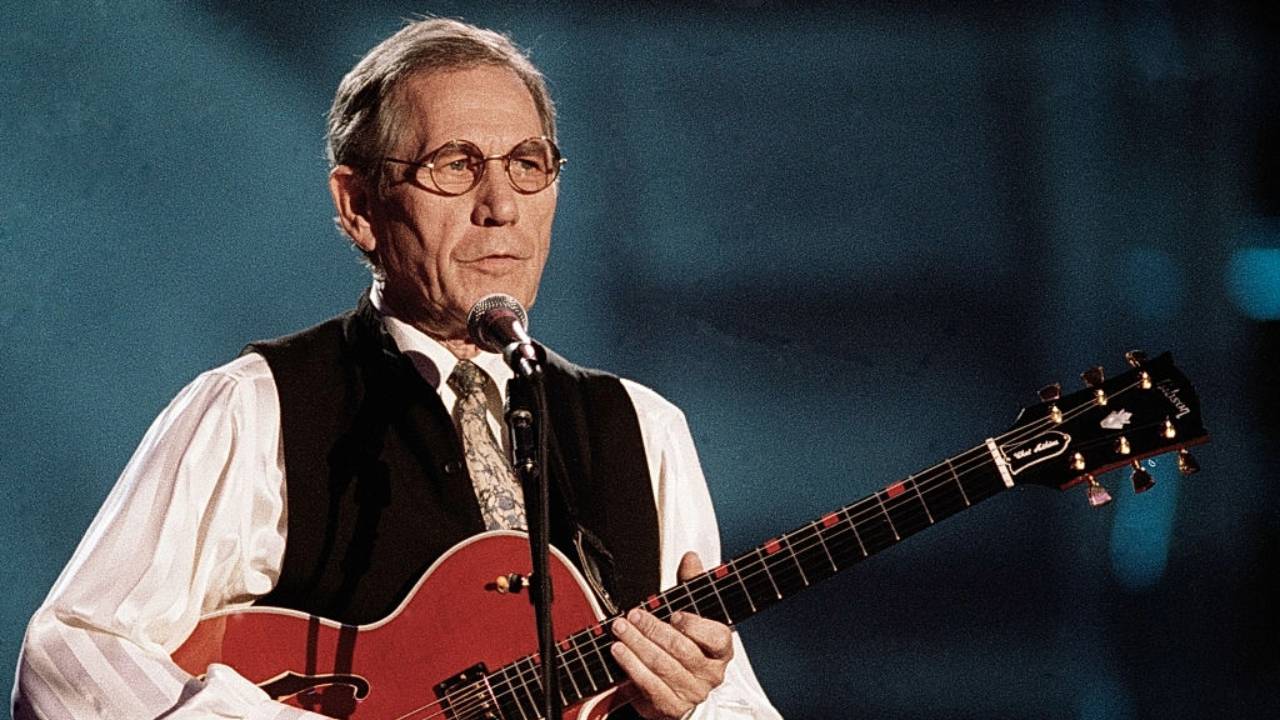

And some of the music was superb. The Band's Richard Manuel delivers a mesmerizing performance of "I Shall Be Released." Levon Helm's supercharged rendition of "The Weight" is a potent reminder of just how good the Band were.

And Janis Joplin bowls you over with versions of "Cry Baby" and "Tell Mama" that have lost none of their power over the years.

Watching Jerry Garcia of the Grateful Dead jamming on an acoustic version of "Better Take Jesus' Hand" with Joplin reminded me of how both of them sprang from country roots and never really traveled very far from them in achieving rock stardom. And, of course, the Band were about as country as a rock band can get.

There's some now-heart-wrenching footage of poor doomed Rick Danko of the Band leading a drunken, stoned but joyous sing-along of the old Texas folk-country song "Ain't No More Cane" with Joplin, Garcia and Weir. There was an openness and innocence running through the whole documentary that would soon evaporate in much of the music scene.

Perhaps tellingly, in an audience Q&A session after the Nashville screening, neither Bonnie Bramlett (of Delaney & Bonnie) nor Bernie Leadon (who was in the film as one of the Flying Burrito Brothers) could recall if they actually got paid for taking part in the traveling music festival. Bramlett noted, almost in passing and perhaps jokingly, that neither her marriage to Delaney nor the marriage of Ian and Sylvia Tyson survived the train ride.

Also very tellingly, Bramlett says one reason there's so much drinking in the movie is that the artists were afraid to take drugs into Canada. In the movie, Weir jokes that drinking was a new experience for the Dead. Bramlett said Garcia finally flew in his friend, LSD scientist Owsley, with a supply of acid. Bramlett pointed up at the movie screen behind her and said, "I wasn't joking about drugs, though. Most of the people you saw up there are dead now."

The Festival Express tour ended on July 4, 1970. On August 15, Joplin went back to her hometown of Port Arthur, Texas, for the 10th reunion of her graduating class at Thomas Jefferson High School. I interviewed her at that reunion for Rolling Stone, and Joplin was still raving about her Canadian train trip as the greatest party of her life and one she couldn't wait to repeat. Then, on Oct. 4, Janis Joplin died of a heroin overdose at age 27. (Pink has signed to portray Joplin in Penelope Spheeris' tentatively-titled movie The Gospel According to Janis this year. A second Joplin movie project is reportedly also underway.)

Besides Joplin, other Festival Express fatalities are the Dead's Jerry Garcia and Ron "Pigpen" McKernan and the Band's Rick Danko and Richard Manuel. The music itself remains very much alive, although just how free it is remains open to debate.