Ten Years Later, "John" Remains Country's Prime Comment on AIDS

Country music deals with all manner of pain -- from bleak poverty to broken hearts. But it has paid relatively little attention to one of the great plagues of our time: AIDS. When World AIDS Day is commemorated Wednesday (Dec. 1), the truth is that country can summon up only a handful of meaningful statements -- lyrical or symbolic -- about this still-rampaging disease.

Kathy Mattea was one of the first country artists to make such a statement. In 1992, the two-time CMA female vocalist of the year let it be known that she would be wearing a red AIDS-awareness ribbon on that year's CMA Awards show. And despite some initial huffing and puffing from CMA officials, that's exactly what she did. Two years later, Mattea spearheaded the Red Hot + Country album to raise funds for AIDS education.

Red Hot + Country featured cuts -- although not specifically AIDS-related songs -- from Johnny Cash, Suzy Bogguss, Nanci Griffith, Dolly Parton, Mattea and several others. The album featured Mary Chapin Carpenter's performance of "Willie Short," a song her producer, John Jennings, was inspired to write after reading a magazine article about AIDS deaths. During that time, Carpenter also wore a red ribbon at nearly every public appearance, including the CMA Awards.

In April 1994, a few months before Red Hot + Country came out, MCA released the Reba McEntire album, Read My Mind. Nestled among the 10 songs was one enigmatically titled "She Thinks His Name Was John." But when you listened to it, there was no enigma in its message. It was about a woman dying from AIDS she had contracted during one night of spontaneous and anonymous sex. "And in her heart she knew that it was wrong," the lyrics said, "but too much wine and she left his bed at dawn/And she thinks his name was John."

"I had the idea for a long time -- with that title," says Sandy Knox, who co-wrote the song with Steve Rosen. "It was influenced by my brother's death from AIDS. In 1979, while my brother was going through chemotherapy for testicular cancer, he received a blood transfusion -- long before AIDS was even on the radar. About five years later, we found out that the person that had given him the transfusion was HIV positive. It was one of those rare flukes. My brother was 29 years old when he passed away, and I put myself in his position if I had gotten that news. ... I wrote it from the standpoint of all the things that he was going to be missing -- having a child, getting married, all of those things."

Because Knox was so close to the subject, she felt she needed a co-writer to transform the experience into a song. But it wasn't easy finding one, she says, "because it wasn't going to have a happy ending and it was not going to be radio friendly. I had about 16 pages of lyrics. I had the girl sitting in a restaurant at first after she got the news. I had her meeting a carnival worker. I had all kinds of scenarios. ... Steve Rosen at that point was playing in my band. He and I had written some other stuff. He was young enough and not jaded enough not to turn down a song idea."

Although McEntire had recorded other of Knox's songs, Knox didn't have her in mind when she wrote this one.

"One of the song pluggers at [my publishing company told me] that Bonnie Raitt was looking for some new songs, songs that were socially conscious," Knox recalls. "I told the plugger about this idea I'd been sitting on for years. She said, 'Why don't you write it, and let's see what happens.' So I wrote it, actually, with Bonnie Raitt in mind. We did three different demos, all piano vocals. We did one with me [singing] it, one with one of my background vocalists, Etta Britt, who had more of a Bonnie Raitt/Janis Joplin-type voice and then another by Greg Barnhill, who had very much of a rock 'n' roll/Rod Stewart-type voice."

As it turned out, Knox never had the chance to pitch the song to Raitt.

"The next week," she continues, "Reba was coming in to look [for songs]. She asked if there were any new Sandy Knox songs. The plugger said, 'Yeah, we do have some, and there's one in particular. But if I play it for you, you have to promise you'll listen to the whole thing.' Reba said, 'OK, I will.' Halfway through it, she got it and teared up and said, 'I'll put that on a very hard hold.' So the song was pitched only one time -- right out of the box. It was never, ever supposed to be a single. But it started getting legs on its own. And it started climbing up the charts on the tail of one of my other Reba hits, 'Why Haven't I Heard From You.'"

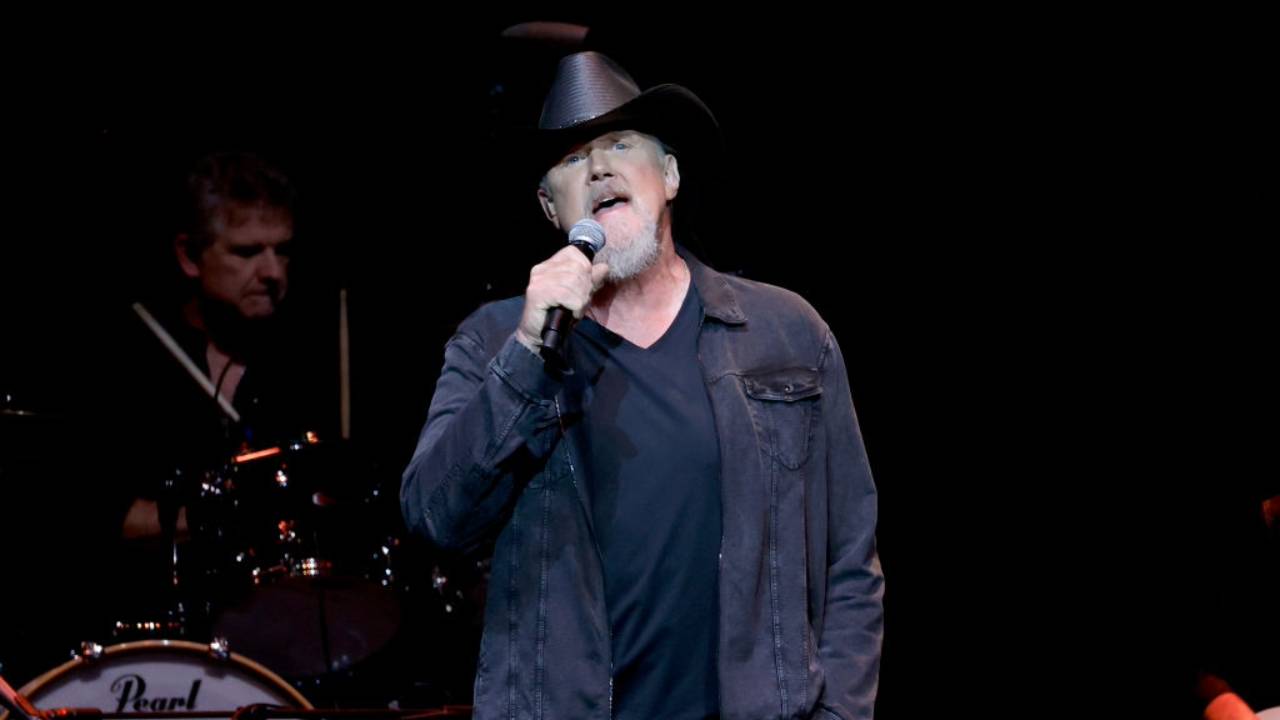

McEntire was used to taking on controversial subjects. By the time she recorded "John," she had already sung about illegal immigration ("Just Across the Rio Grande"), domestic abuse ("The Stairs"), mercy killing ("Bobby") and neglect of old people ("All Dressed Up With Nowhere to Go"). So AIDS was not taboo.

"I was big advocate and fought to get that single put out," says Scott Borchetta, who was then emerging as the bright star in MCA's radio promotion department. "They didn't want to put it out. So I had to kind of jump up on the table. A lot of people didn't get it at first. There was resistance at radio, but it was one of those songs that [made] such a big impact that once we got it by the gatekeepers, it was a huge response, and it was a big seller."

"She Thinks His Name Was John" entered the Billboard charts on July 30, 1994, where it would remain for the next 20 weeks. However, the song, as Knox observes, wasn't totally embraced by country radio programmers. Despite the fact that most of McEntire's singles had gone Top 5 or better during the previous 10 years, "John" peaked at No. 15.

But the fan response was overwhelming, according to Knox and Jennifer Bohler, who was McEntire's publicist at the time. "She did get a lot of mail -- this was before e-mail," Bohler says, "and none of it negative, as I recall." Knox notes that she got so many calls for interviews and comments -- ranging from local newspapers to National Public Radio -- she hired an assistant to help handle them.

Although she has had songs cut by Patti LaBelle, Neil Diamond, Liza Minnelli, Donna Summer and Dionne Warwick, among others, Knox says none of those cuts came close to generating the interest "John" has.

"It's the one song that's gotten more press and that people remember," she reports. "They remember where they were the first time they heard it and how it affected them -- especially [those who had] children who were starting to date."

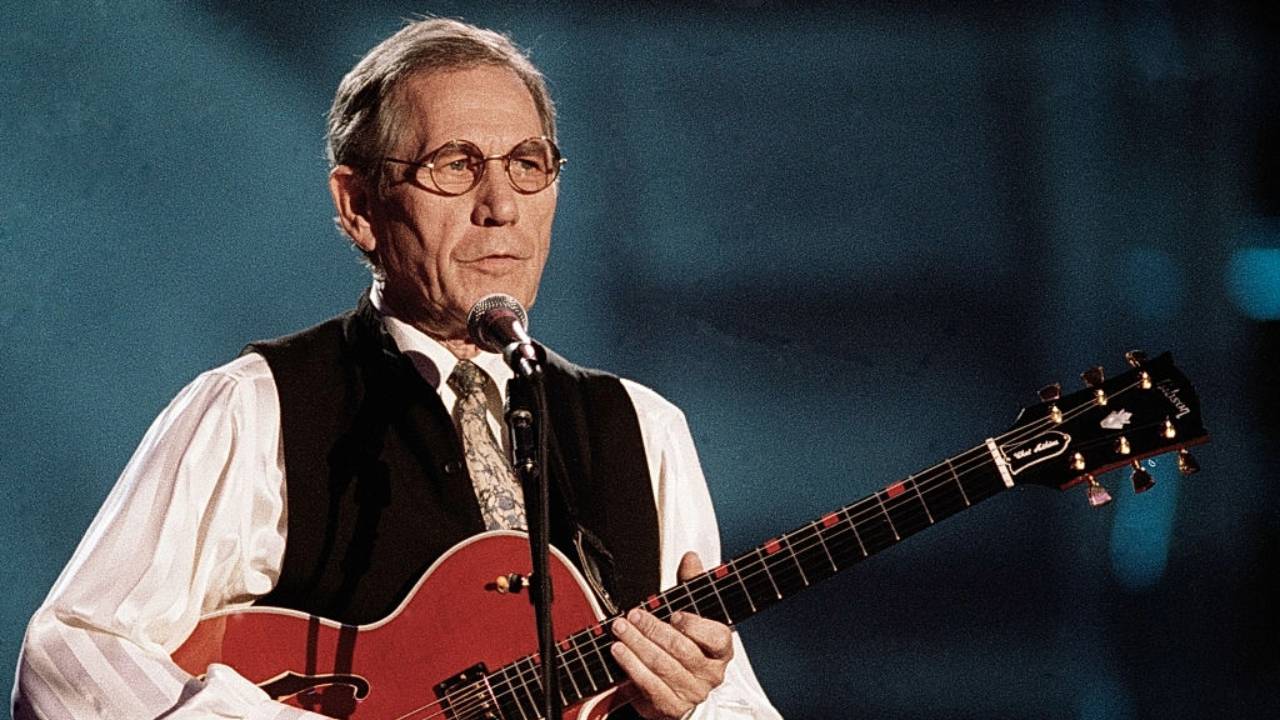

Clearly, McEntire's recognition of the AIDS problem didn't spark a trend in country music. But it hasn't been the last word either. In 2001, Rodney Crowell took up the theme in his album, The Houston Kid. Two songs in the collection focus on the disparate lives of twin brothers. "I Wish It Would Rain" is the ramblings and self-recriminations of the brother who has been "turning tricks on Sunset," a "cracker gigolo" now dying of AIDS. "Wandering Boy" is the response of his once-homophobic brother who has remained in Texas and now stands ready to accept and comfort his prodigal twin. While Crowell's songs are as direct and uncompromising as "John," they haven't enjoyed nearly as much airplay.

In the end, it may be the fear of getting little or no lucrative airplay -- as much as it is timidity or aversion -- that keeps country writers and performers at such a distance from AIDS. It can't be the lack of drama.