In the Words of Tom T. Hall ...

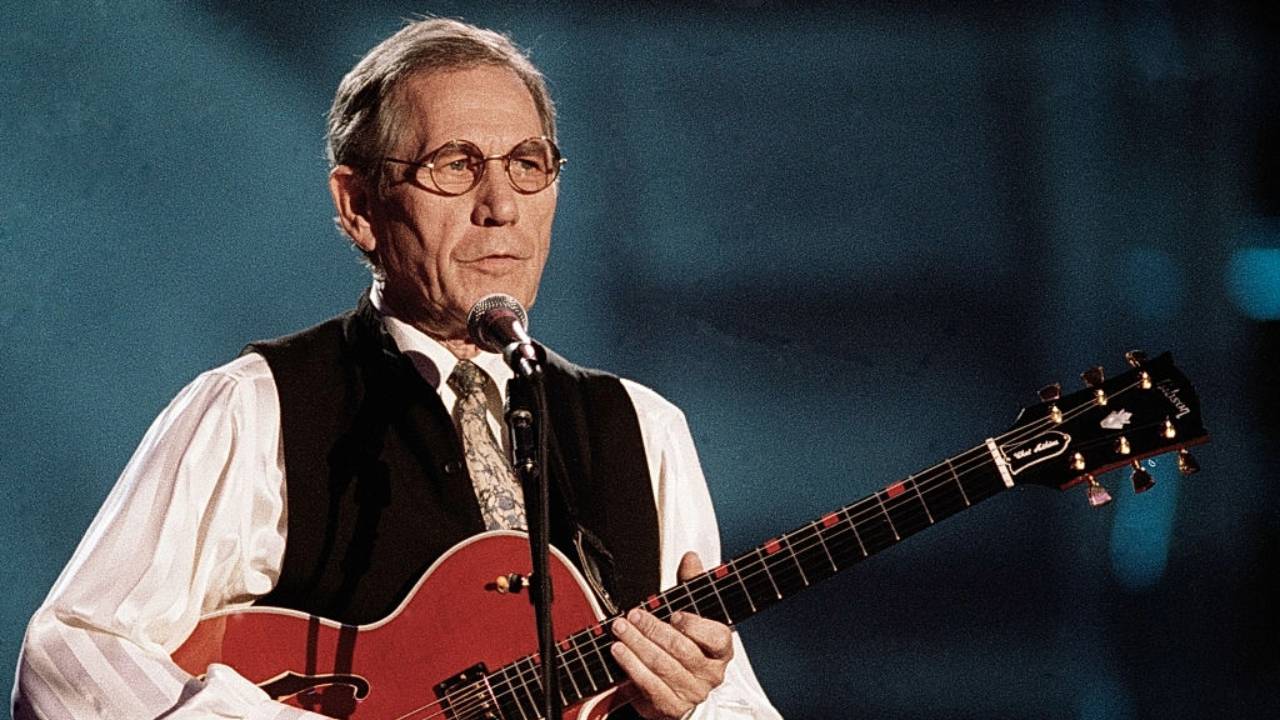

Although he's serious about his retirement, Tom T. Hall finally agreed -- after two years of arm-twisting -- to serve as this year's artist-in-residence at the Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum.

"My wife, whom we affectionately call Miss Dixie, said, 'Look, if you do this, we won't bug you with the details. Just show up and be witty and charming,'" Hall says with a laugh. "I had three people produce the things because I'm not much for getting out the phone and trying to get people out of the house."

The first of three performances takes place Wednesday night (Aug. 3) when Hall's life story will be told through the words of his songs, sung by his famous friends and admirers. On Aug. 10, the evening is billed as "Songs I Wish I'd Written and Some I'm Glad I Did." He concludes the series on Aug. 17 with a night of bluegrass.

Here, "The Storyteller" talks to CMT.com about the inspirations behind some of his biggest hits and songs he wrote that became hits for others, including Jeannie C. Riley's "Harper Valley P.T.A." and Alan Jackson's "Little Bitty."

CMT: What comes to mind when you think of "Ballad of Forty Dollars"?

Hall: The first job I ever had, I got a paying job with my aunt who was the head of the cemetery committee. I got a job mowing grass up in Olive Hill, Ky. Of course, when they had a funeral, I had to shut down the mower. ... That song is about my experiences shutting down the mower and watching the funerals. The irony is, when somebody else dies, I don't know how it got to be this way, but the rest of the world more or less forgives their sins. They say, "Oh, he was a wonderful guy, a good person," which is one of the ironies of philosophy, I think. Then when they were digging the graves, the people digging the graves had a lot of conversations about the economy of dying. You know, "He's got a brand new pickup. Who's going to get that?" Then it comes down to, the fellow owes me 40 bucks, and you're certainly not going to go to the widow and collect it. I guess it's lost. So that's where the song came from. I wrote a lot of those songs from personal experiences.

What about "Homecoming"?

My father was a Baptist preacher, kind of what I'd call an ordinary person. But if you've got a son that wants to go off in the music business, it's pretty hard for them to grasp that. And when you come home after being out singing, they don't get exactly what you're doing. Everybody liked music, but nobody took it seriously and never thought of it as a profession. So when you come home, it's hard to explain what you're doing. It's about a son who comes home and tries to explain himself to his father.

For instance, I was offered a job managing a department store. My father thought, "My son, a department store manager!" You know, "A 50 percent discount on khakis!" (laughs) He just lit up. I said, "No, I'd rather pick and sing." It's hard to get that across -- what you're up to.

One of my favorites is "Margie's at the Lincoln Park Inn."

It's a little bit like "Harper Valley P.T.A." It's about the reputation. It digs a little deeper behind what's obvious. The guy's a Boy Scout counselor, he teaches at Sunday school, his wife belongs to the bridge club, he's capable of fixing his little boy's bike ... and all of this. But behind that façade of domesticity and civility, Margie's at the Lincoln Park Inn. That's a big story there.

I think it goes back to reading Sinclair Lewis, who's largely forgotten now. I was really influenced by Babbitt, Main Street, Elmer Gantry. He really was a voice of that time.

We have to talk about "Harper Valley P.T.A.," of course.

It's a true story. I was just a fly on the wall. I was only 8, 9 or 10 years old at the time. I was mowing grass around the neighborhood -- it sounds like I should have turned into a landscaper. The lady was a really free spirit, modern way beyond the times in my hometown. They got really huffy about her lifestyle. She didn't go to school, but they could get to her through her daughter. She took umbrage at that and went down and made a speech to them. I mean, here's this ordinary woman taking on the aristocracy of Olive Hill, Ky., population 1,300. When I was a kid, you just didn't take on the aristocracy. It was unheard of. They were [supposedly] right about everything.

Did you every encounter her after that?

No. I certainly didn't use her real name. Out of 1,300 people, you could pick her out real quick. So a lot of things I wrote biographically. I changed the names of people.

Was the character in "The Year That Clayton Delaney Died" based on someone named Floyd Carter? I've read varying accounts on that.

No, his name was Lonnie Easterly. I used to travel and look for songs. That was my alias, Floyd Carter. If I was out looking for songs and they'd say, "Aren't you Tom T. Hall?" I'd say, "No, I'm Floyd Carter." I never told many people that. I didn't have to use it a lot. I'd get in my car and drive through small town America and stop off at little cafes and pool halls, to look and listen. I got a lot of songs that way. There toward the end, it got to where people would recognize me.

But Lonnie Easterly was his name. The way I got the name Clayton Delaney, it's a good story. The hill he lived on was called Clayton Hill, and the people who lived next door to him were the Delaneys. So I didn't want to move too much geography around and lose the feel of what I was writing about. So when I changed his name, I changed it to a hill and a neighbor. I kept everything on that hill, there in his neighborhood, to keep from losing that reality.

Another song that a lot of people remember is "I Love."

Yeah. Irony of ironies, it's been my biggest moneymaking song. Let's see, Little Debbie Cakes bought it for a commercial, Ford Trucks used it for a commercial and then Coors Beer used it for a theme song the last couple of years. It's been recorded by a lot of orchestras. You hear it on the elevators, which is amazing. It's just three chords, and it's only two minutes long. For some reason, I walked into a great melody. [He sings the melody.] It sounds almost like what Mozart would have done or Chopin. I got really lucky on that melody, and it's been used for a lot of different things.

How about "Little Bitty"?

I was in Australia. I like physical activity. I like to do manual labor. It's force of habit. I'm a country boy that's been in the military, so I can't vegetate very well. When I was in Europe, I could walk, which is great. Australia, England, New Zealand, France -- places like that they have bicycle paths. We don't have them here. And you can walk for miles without getting run over. So I was in Australia and I went walking, and I wound up out in the country. I walked past this little house. It was a little five-room house painted white with shutters, a picket fence, a car in front of this little wooden garage and a little dog in the yard. I thought, "I'm in Australia, and here's the great American dream." The house with a picket fence, the dog, the flowers. It was almost like a painting. I said, "This is universal, this notion of having a contained domestic situation."

I thought, "So, it's all right to be little bitty." Then as I'm walking, I start writing the song, describing this little bitty house and the little bitty yard with the dog. But I went back to the hotel where I was staying and I'm viciously awake early. Working with musicians, it drives them crazy. You're getting up as they're going to bed. They just resent the hell out of that. But anyway, I'm going back and now they've finally opened the coffee shop and I'm going to get a cup of coffee. I'm sitting there thinking, "Well, it's a universal idea, but ..."

I called the waitress over, and she brought some coffee. I said, "May I ask you a question?" and she said, "Certainly." I said, "Does 'little bitty' mean anything in Australia?" She said, "Oh yes, it's something very tiny!" I said, "Good. Thank you very much." She looks at me kind of quizzically, like "What the hell is this all about?" But now I know they know about it in Australia, and they know about it in England and all the English-speaking countries. I thought maybe it was something I learned in Kentucky. Some of those things you bring out of those hollers and take them out into polite society and they have no idea what you're talking about. So when she said that, I went upstairs and got my guitar and finished the song.

But then it laid around in a drawer for two years because it didn't have a last verse. It stayed in that drawer. We moved to Florida, and I emptied my briefcase in a drawer down there. I went to do a demo and I didn't have any songs. I got that song out of the drawer and looked at it -- and no last verse. I said, "Well, after two years, I know how this thing ends. The way it started!" It starts all over again. It's a cyclical song. I wrote the last verse at the bottom of the typed page. I demoed it and put it on my little album [1996's Songs From Sopchoppy]. Then Alan Jackson heard it. I'm glad I never emptied my briefcase into a wastebasket. It's a dangerous business, what you throw away.