John Fogerty Embraces His Past

If music industry veterans were to count the miracles of 2005, somewhere near the top of the list had to be John Fogerty's renewed involvement with Fantasy Records and the release of The Long Road Home: The Ultimate John Fogerty -- Creedence Collection.

Fogerty's return to the label follows a lengthy, well-publicized and downright nasty legal dispute with Fantasy's former Saul Zaentz, who acquired the company during CCR's heyday. And what a heyday it was: A string of American music classics including "Proud Mary," "Bad Moon Rising," "Who'll Stop the Rain," "Green River" and "Lodi," just to name a few. In 1969, the band sold more records than the Beatles.

After creating some of rock 'n' roll's most enduring music, however, Fogerty's bitterness over royalties and Zaentz's ownership of his songs caused him to go more than two decades without performing any of the material he had written, sung and recorded as CCR's leader. After an epiphany at Robert Johnson's gravesite, Fogerty finally started playing the old songs again in the '90s -- much to the delight of his longtime fans.

In 2004, Fantasy was purchased by the Concord Music Group, whose owners include legendary television producer Norman Lear. Comfortable with the company's leadership and pleased by an improved business arrangement, Fogerty is clearly happy with the release of the 25-song The Long Road Home, the first CD to feature CCR hits alongside his solo material, including the 1985 hit, "Centerfield."

Fogerty may never totally get over his feelings toward Fantasy's old regime. However, in a recent phone interview with CMT.com, the cheerful, upbeat tone of his voice seems to indicate that he's more comfortable than ever with the past.

CMT: Through the years, you were involved in several contracts with Fantasy Records, but weren't you still a teenager when you signed your first deal with them?

Fogerty: When I walked in the door there for the first time, I was 18 years old, and I believe we probably signed a contract then or maybe at 19. Then again, there was a later signing, and that's what basically did me in.

Most musicians can't see any farther than getting their first record released. Was that pretty much your attitude to begin with?

Oh, yeah. The first one [contract], especially, in that weird way, that sort of sense of denial that children go through. When you're young, you think you're immortal, right? They're gonna live forever, and you can't tell them anything. I'm sure I had big doses of that. As you say, it's all important to just have that guy's attention right now. (laughs) If some big guy at a record company is going to put your record out, boy, you don't want them to forget about it before he goes on to something else. So you're just thinking that everything will be solved if you can just get this record out. And then, hopefully, it will be a hit, and everyone will smile and take you more seriously.

The music industry wasn't nearly as sophisticated back in the '60s and early '70s. It seems like a lot of artists really had no one trustworthy to turn to when it came to handling their business affairs.

Oh, that was certainly the boat we were in. We didn't have access. We didn't really have a lawyer, like a plumber in the family that you just call up every time the pipes break. We didn't have that at all. [CCR bassist] Stu Cook's father was a lawyer, nothing to do with the music industry at all. ... Stu was supposed to show the contract to his dad. But like all young people, I think he really didn't. I think he just came back and told us, "My dad says it's OK to sign." ... The first contracts were signed in that spirit of, "Well, gosh, we'll sign this so we can get our record released."

For the later ones, just to give you an insight, the earlier contract was under the first ownership of Fantasy Records. And then Saul Zaentz and some partners purchased Fantasy Records somewhere around October of 1967. Saul was the sales representative during the early days when we were walking in there as teenagers. He was the only one who didn't speak in beatnik talk. Everybody else there were kind of old beatniks from the early '50s.

Fantasy was a jazz label.

They were jazzbos. That was kind of their world, where Saul seemed more from the business world, at least. So we regarded him as our friend.

[Editor's note: When the phone call is temporarily disrupted by static on the line, Fogerty laughs and jokes, "The heavens just came unglued when I said, 'We regarded Saul as our friend.'"]

Anyway, that was the truth at that time. So when Saul purchased the company, we trusted him. Which is the unfortunate truth. We thought we were all in there on the ground floor. ... Again, not having access to a lawyer, because a lawyer probably would have said, "Whoa, let's make sure we've got all these things we're talking about in writing." Of course, none of them were.

All told, can you estimate how much the legal dispute with Fantasy has cost you?

I can only just say, "In millions." Literally, probably tens of millions of dollars. It's so big. And for a guy who came up as a lower middle class kid ... so much of that money just went to Fantasy instead of going to me. ... And also, as artists, we were at the bottom of the barrel as far as what we were paid. All of that money went to Fantasy. ... The most crushing part, the part that was very hard -- that was worse for my career and for my personal life -- was that I still owed them so many records after Creedence broke up. All the other members were set free immediately, but I was retained. And so this thing stretched out into my future, basically for the rest of my life. That was the part that just crushed me. ... Immediately after Creedence broke up in '72, they informed me, "We have the rights to your recordings in the future." It was basically 36 masters -- plus 10 -- if I remember this correct -- every year.

Good Lord!

That means tracks. That means songs. Thirty-six, plus 10. I still owed them five more years of that. So if you add that up, 46 tracks is probably more than four albums, at least at the way Creedence was making them. We usually had about seven or eight tracks on our records. To come up suddenly with 46 of them, that's something huge. They had a provision that for any year that I didn't provide those, the unprovided tracks slid over into the obligation for the next year. And if I didn't provide it in that year, then it all slid over into the next year. So I basically saw myself going on for 28 or 30 years, something like that. It was undoable. At some point, I just caved in. I melted down. At about 1973, I went in [and said], "I can't do this. It's so oppressive. My brain can't ... I'm not writing songs anymore. I'm thinking about this."

This was an extremely public battle. Do you think the publicity has changed things for the better in the music business?

I suppose. I just hope that young guys think, specifically. Unfortunately, you never think that those people in the room with you are the guys that might turn out to be your worst enemy. You're standing there going, "Oh, yeah, we all understand. We're gonna do these things." But if it is not written down in the way that you're just talking about it -- that means you have to go get your lawyer that represents you, not his lawyer that represents him. You've got to treat it much more like divorced couples go through things. Suddenly, even though they were lovers and best friends, now they're enemies.

The liner notes of the new CD talk about you coming to terms with performing the old songs while you were visiting the Mississippi Delta. Was that like a bolt of lightning, or did it take some time for the idea to sink in?

It was exactly like a bolt of lightning. This happened in 1990. I ended up taking several trips into Mississippi, just wandering around the way a guy would who was writing a book. I was acting much more like that. When I first went, I didn't even know why. I kept getting this sort of urge. I always say it's sort of like the guy in Close Encounters of the Third Kind when he's building the mashed potatoes on his dining room table, and he doesn't know why he keeps humming these notes to himself. (laughs) So I finally started going to Mississippi, and I basically landed with no plan. But I eventually started buying a lot of music and doing a lot of reading, mostly about the old blues guys. That seemed to be my focus.

And one day, I'm at the purported gravesite of Robert Johnson. I'm just mulling over Robert's great career and the mythical, legendary 29 recordings that he had made. Basically, I'm looking right at a big tree that seems to be where Robert was long ago buried. And I'm thinking about how these songs are very vital now. Remember that 1990 was within probably a year of the big [Robert Johnson] boxed set that got released and went platinum. I thought, "I wonder who owns the rights to those songs." And then I got this very negative image. I thought, "It's probably some lawyer" -- some unsavory type in a tall building in New York City with a big cigar. I thought, "God, we always get screwed. That really stinks."

And then I just shook my head. Very emphatically, I said to myself, "It doesn't matter. Those are Robert's songs. I'm standing here with Robert Johnson, basically, at his gravesite. He's the spiritual owner of those songs." That's literally the phrase I born to myself. And at that moment, that's when the lightning bolt hit. My eyes got real wide, and I thought, "That's just like you. Do you see it? You're the spiritual owner. No matter what you've gone through, you wrote those songs. You created them. You lived those songs, and you're the one who really can sing those songs with the true understanding of how they came into being." It doesn't matter about the mythical tall building and the crooked guy with the big cigar. Robert's story was just like mine, and that was when I made up my mind.

Can you remember the first few nights when you started performing those Creedence songs live?

It would have been after the Blue Moon Swamp album came out. Understand, I basically went for 25 years without performing those songs. Even I didn't realize it had been that long, but it was from 1972 until 1997. There was only one exception. I played on the Fourth of July in Washington, D.C., in 1987. I gave a special concert for veterans, and I started the show with the riff from "The Old Man Down the Road" ... and then I went into "Born on the Bayou." It was kind of mind blowing. Everyone knew I wasn't playing my old songs. But this was kind of a gift to the veterans and kind of symbolic to me. Even still, I went another 10 years without publicly performing those songs. So I had made up my mind in 1990, but I actually was not out performing in front of people until 1997.

Once you did the Blue Moon Swamp tour, did you feel a sense of relief to be able to perform those songs onstage?

Yeah. I was happy. I was totally into it, but everything was new. I was touring again and playing my old songs and supporting a new record, which was kind of a rare occurrence because there had been so much time between records. My audiences, in the beginning, were full of boomers. You'd see a lot of 45 or 50-year-old males, particularly at that time. But, I must say, a lot of those men were crying, too, so it was a very emotional thing. I can't be sure, but I heard that quite a few of them were Vietnam veterans, so that was one of the reasons why they were there. As time has gone on, the audience has gotten more like a normal slice of the American culture -- and beyond -- very mixed ethnically, also certainly male and female and going all the way from past 60 to below 10.

Was Norman Lear's involvement with the new Fantasy company a major factor in returning to the label?

I would say yes, certainly initially. I have a very positive image, I think, of Norman. As most people who have ever seen a sound bite or a little bit of an interview, he just seems very at peace with the world. It just looks that way. It's certainly a way I would love to feel about the universe. It's almost like he knows something that the rest of us don't know. But he's not really in the day-to-day running of my involvement at Fantasy. He owns Concord Records, and Concord acquired Fantasy in a really neat irony of the old days. Back in the Bay Area in the early '70s, Fantasy was the big independent guy, and Concord was an even smaller jazz label. Of course, Fantasy was a big label because they had Creedence Clearwater. But in a neat turn of events, Concord acquired Fantasy. The folks at Concord/Fantasy have turned out to be very delightful people. And that's really the reason why I'm there.

How difficult was it to condense your song catalog to just 25 songs for the new CD?

Their scenario for this record was that they wanted to limit it to 25 -- the idea being that it could be one CD and a simpler package. If you start getting many, many more songs or two CDs, you're getting very close to the idea of a boxed set. Which I would love to do eventually. Most other major artists have long, long, long ago had a boxed set. But that would have meant delaying the whole thing for a much longer time. You've just got to get a lot more people involved and take more time. ... Certainly from the Creedence era, most of those songs just kind of jumped right out. And then from my solo career, many -- if not most of them -- also jumped right out.

What are you working on at the moment?

The next thing will be a DVD, which we've already recorded. A live concert. But I haven't even seen the footage yet. I've listened a little bit to the music, which sounds great, but it's all in its raw form.

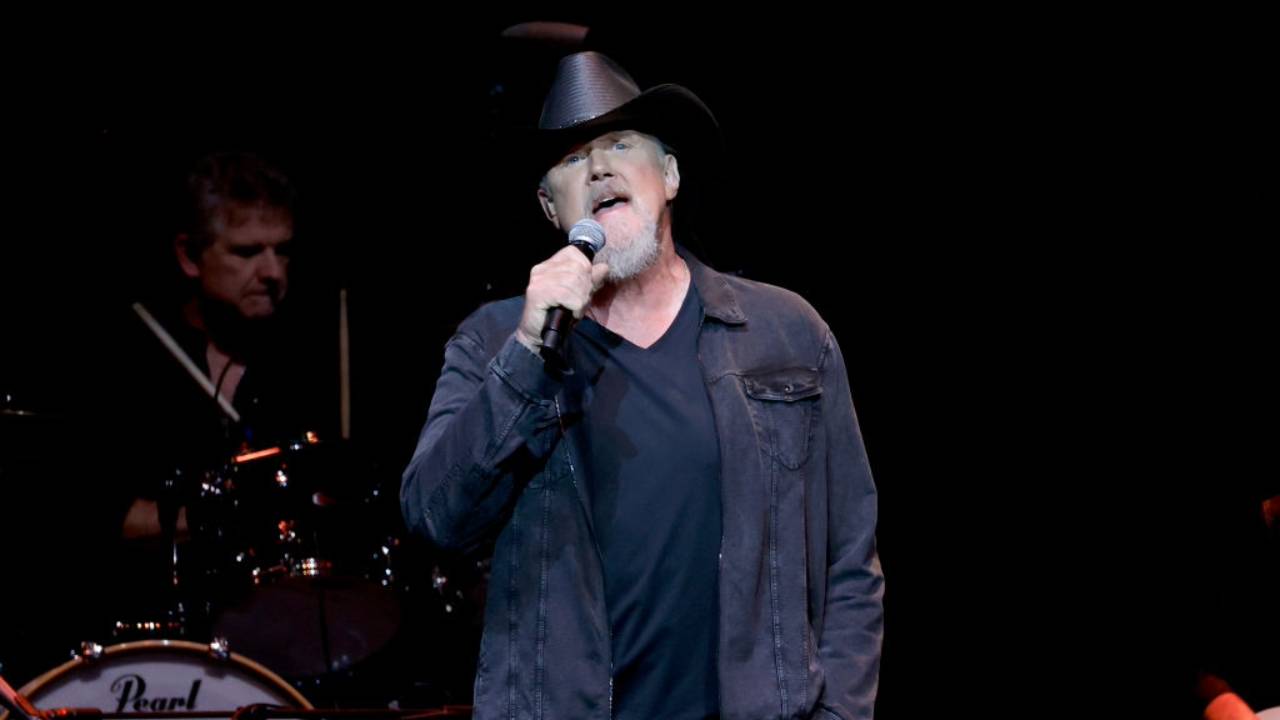

You and Keith Urban taped an episode of CMT Crossroads in Los Angeles. What kind of response have you gotten from that?

It's been a very, very good and positive response. ... Keith is a wonderful guy. I consider him a friend. That started out as a project, and I didn't know a lot about Keith. But I went and met him and saw one of his shows here in the L.A. area. I immediately became a big fan. Since then, of course, I've listened to all of his records. He's an absolute great guitar player, and I'm a huge fan of anyone who can play the guitar. He turned out to be just a nice guy. We had a lot of fun putting that show together and delving into each other's music and figuring out how we were going to present ourselves onstage, singing and playing with each other. That's one of the highlights of my career. It really is. I hope, at some point, to get to do some more work with Keith.

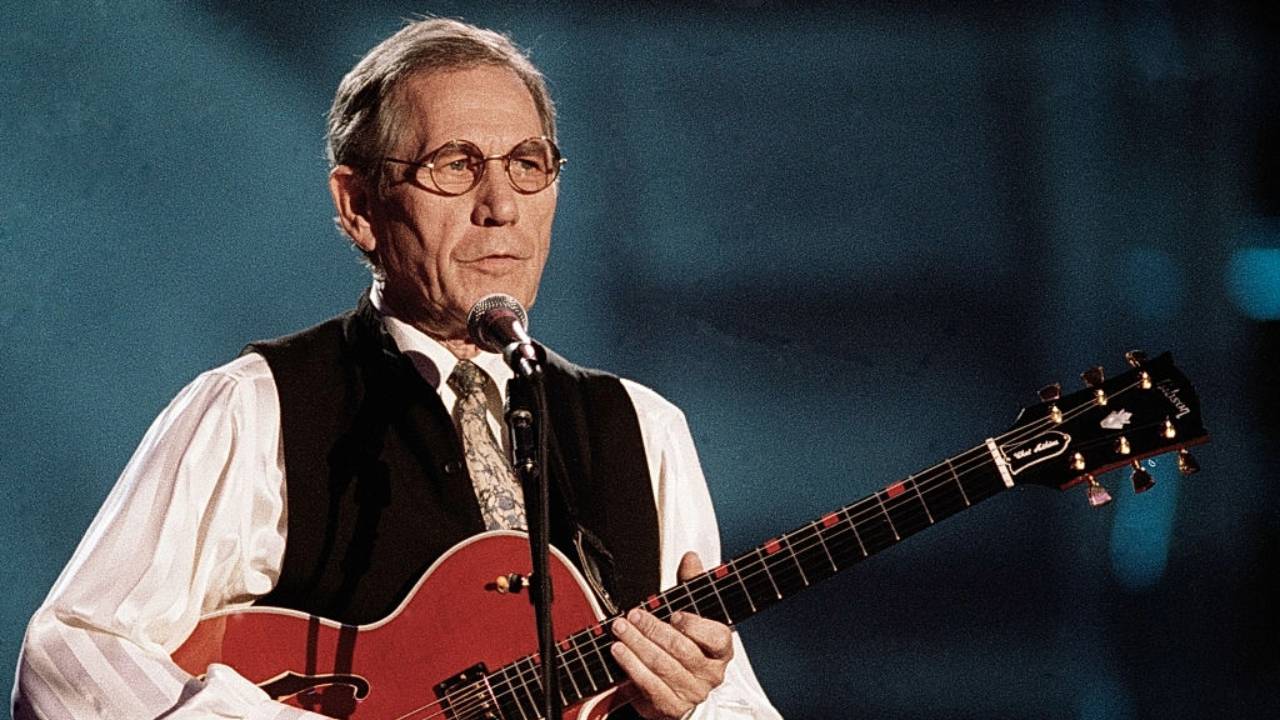

Do you listen to mainstream country music these days?

A little bit. I get to hear the country channel here in Los Angeles. When I hear somebody's having a hot career, I'll go buy their CD. I'm a huge fan, all the time, of Alan Jackson. I mean, I don't have to hear the record in advance. I just buy it. In fact, the last song I play every night on tour just before I come out is "Mercury Blues." Alan is carrying, to me, the eternal torch of what country music is. You can take that in all the ways it means. Country music is in good hands with Alan Jackson, and I never have to worry about how it's being handled. I've long been a Merle Haggard fan. I love the golden era of country music. I think anybody would know that just by hearing me talk or hearing me play.