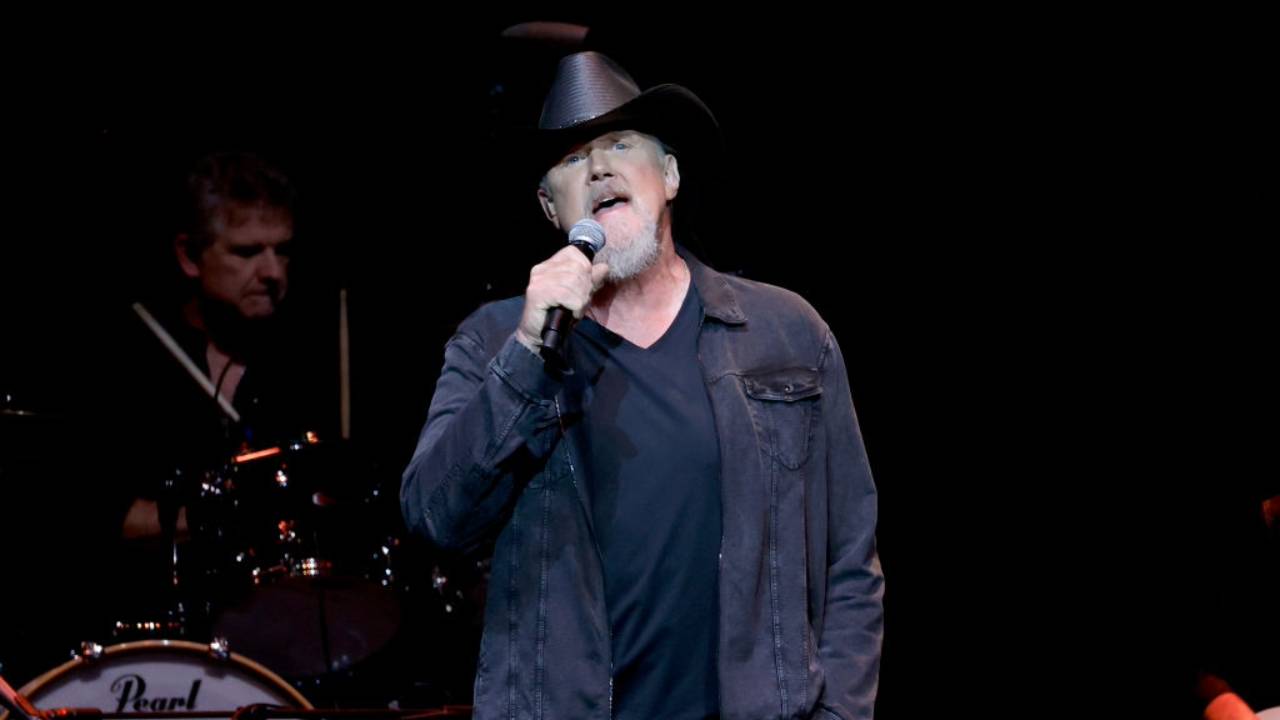

Rodney Atkins' Joys of "Hell"

If you're going through hell, Rodney Atkins says, "Stay cool. It could get better." In the nine years since Atkins charted his first single, he's endured the hell of shifting record-label priorities and all the soul-killing delays that go with them. But now -- with a single in the Top 5 and his second album just out -- things are looking up. Again.

In 1997, soon after he signed to Curb Records, Atkins made his chart debut with "In a Heartbeat," a song he co-wrote. Plans called for it to be followed by an album titled Rodney Atkins. However, except for a few promotional copies, the album never saw daylight.

Nothing else happened, record-wise, until 2002, when Atkins surfaced again with the mid-level singles, "Sing Along" and "My Old Man." Then, in 2003, he hit big with "Honesty (Write Me a List)." This ingratiating ballad floated all the way to No. 4 and provided Atkins the core of his first distributed album, Honesty.

For the next couple of years, it looked like the East Tennessee native might have to settle for being a one-hit wonder. He sidestepped that fate, though, after he heard the demo for "If You're Going Through Hell (Before the Devil Even Knows)," a bit of lyrical philosophy written by Sam Tate, Annie Tate and Dave Berg.

"I loved it," Atkins says. So did Curb. Once the label bigwigs witnessed the song's appeal, they put Atkins' second album on fast track.

"At first, it wasn't like, 'We have to have an album right now,'" Atkins explains, "It was, 'We'll need one in three or four months.' Then, as this single moved, they went, 'We'll have to have it in three weeks.' It was fun. It was challenging to get it finished and to know I was working with a real definite goal in mind."

Arkins co-wrote six of the songs for If You're Going Through Hell and co-produced the album with his longtime friend and writing partner, Ted Hewitt. Had it not been for the songwriting chores he was doing in his home studio, Atkins might still be waiting for Curb to give him the go-ahead.

"[The project] started out with me just doing work tapes and demos and that sort of thing," he says. "The head of A&R at Curb -- a guy named Phil Gernhard -- loved the way the vocals sounded. He called and said, 'Where did you do these vocals? They sound completely different from anything you've done.' And I said, 'I did it at the house.' ... He said, 'Keep doing that. I think the vocals sound so effortless and real. Try that again.' So we would track in Nashville. Then I'd load it on the hard drive and bring it home. Technology has made it simple for guys like me."

This homespun approach was just what Atkins needed to pour his heart into the album. "It was such a comfortable process doing vocals this way," he says. "I'm home. I'm singing when I feel like it. My little boy would be sitting in the floor behind me coloring. It was during the winter when I was working on this. So I could go check the stove and see if I needed some more wood on the fire."

Atkins grew up in Cumberland Gap, Tenn., near the Virginia-Kentucky border. He began searching for a record deal in Nashville while he was still majoring in psychology at Tennessee Tech in Cookeville. "I was traveling back and forth doing writers' nights, playing everywhere I possibly could. I was playing restaurants, bars and shopping malls. One time, I sang at a wedding in a grocery store."

Despite his experience as a performer, Atkins acknowledges he was naïve about the way the music business operates. He was also lucky. He finally talked someone into listening to him.

"I did one of those things where I'm sitting on the steps of [the Curb talent scout's] office waiting for him to show up," Atkins says. "He started by saying, 'We don't need any new male acts.' They had Jeff Carson and David Kersh at the time and Tim McGraw, obviously. I said, 'Let me just play you one song.' He stopped me halfway through the song and offered me a deal. We went into the studio that day, and the next day recorded the song ["In a Heartbeat"] that they put out as a single. I had no idea what was going on. It was a whirlwind."

It wasn't long, though, before the whirlwind died down, leaving Atkins with no wind in his sails. "I went through some bad producer situations," he says, "with people that I don't think were really in it for the music. They were just running [me] through the producer mill. I wasn't really getting the attention it required. I didn't know how to write a song. I didn't know what it was to sing in the studio -- I'd sung live so much. I just kind of got stuck under the bus. Sometimes I wasn't doing anything [with music]. I was working other jobs. I was trying to provide for my family. It's hard to be kicking and screaming, 'We've got to be working on this,' when you're out just trying to make money."

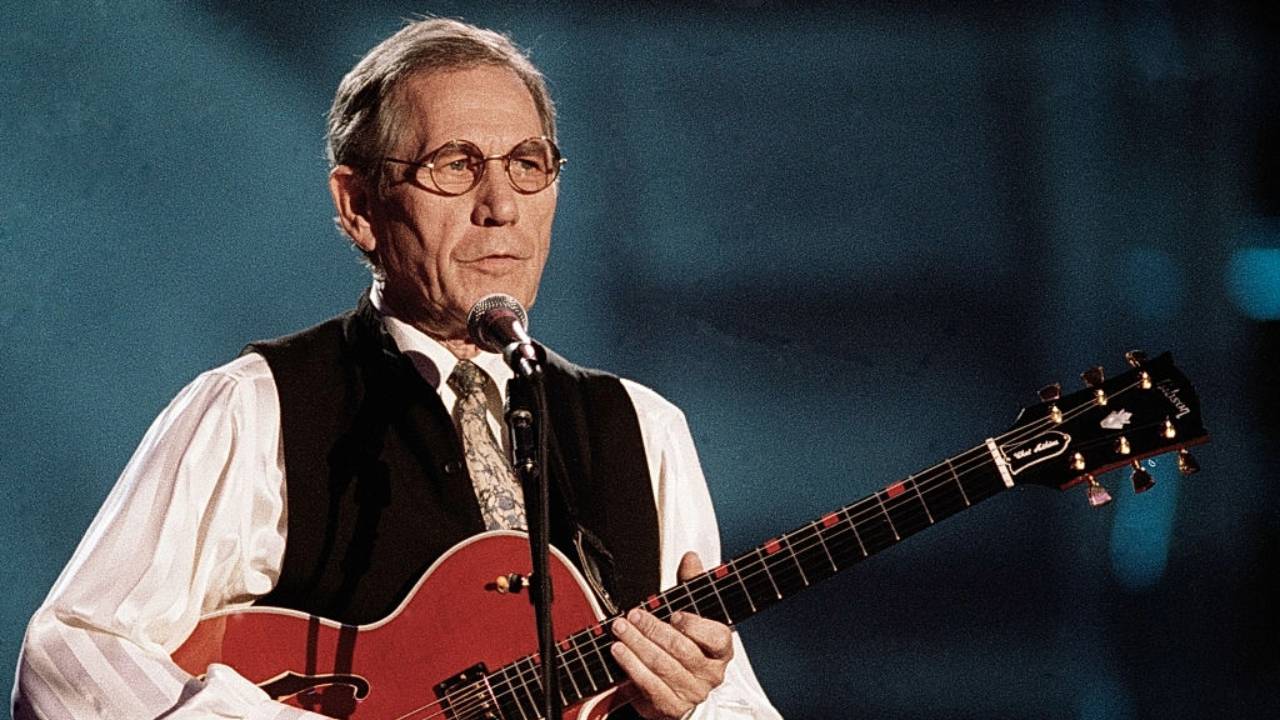

At one point, rock producer Bruce Fairbairn, famed for his work with Bon Jovi and Aerosmith, agreed to take Atkins under his wing. "But with a [busy] guy like that," the singer notes, "it's like, 'Yeah, we'll get together. I'm free in eight months.' Well, a month before we were supposed to get together, he passed away. So there was a year gone."

In recording songs for Honesty, Curb used a variety of producers. Atkins describes it as "kind of an experimental process."

Stylistically, there's nothing experimental about If You're Going Through Hell. It's solidly country. And it holds together well, both sonically and thematically, with Atkins variously casting himself in the roles of affectionate observer ("These Are My People," "About the South," "Watching You"), angry or shattered lover ("Wasted Whiskey," "Invisibly Shaken") and plucky voice of hope (on the title cut).

Whatever his pose, he sings -- with palpable joy and conviction -- some of the cleverest lyrics imaginable. Clearly, Atkins has moved into one of hell's better neighborhoods.