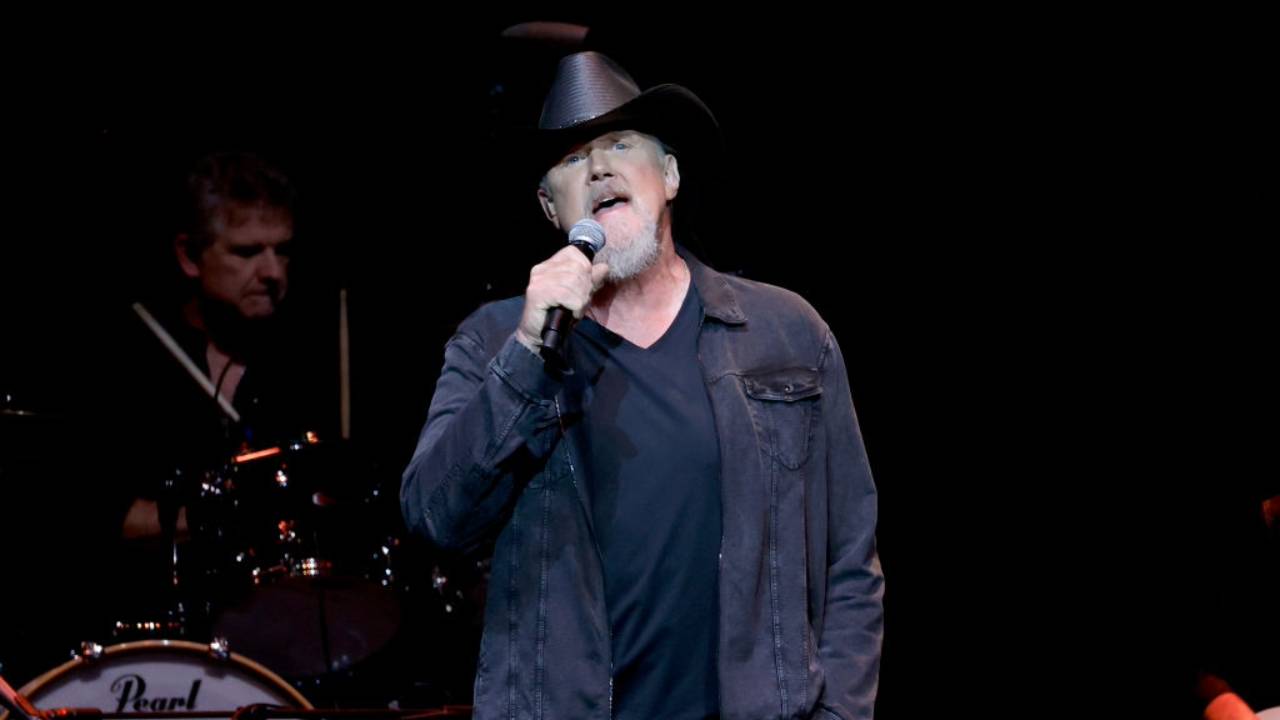

Bobby Pinson Roars Back With 'Songs for Somebody'

Listening to a Bobby Pinson album pretty much trivializes any other music you'll hear the rest of the day. His songs deal with serious stuff -- sin, guilt, redemption, escape, self-identity and the totemic properties of old cars -- and he sings them with such understated intensity that it's like overhearing whispered confessions.

Although he had already established himself as a songwriter for others, Pinson didn't surface on country radio himself until February 2005 when his "Don't Ask Me How I Know" hit the Billboard charts. The song, which came from Man Like Me, stayed on the charts for 21 weeks, ultimately rising to No. 16.

Man Like Me was Pinson's first and last album for RCA Records. In spite of stellar reviews, the label dropped him without releasing a second single.

Since then, the Texas native has found himself in even greater demand as a songwriter, co-writing Trent Tomlinson's "One Wing in the Fire" and Sugarland's recent No. 1, "Want To." He co-wrote the latter with Sugarland members Jennifer Nettles and Kristian Bush. Pinson and Toby Keith also also co-penned "Pump Jack" for Keith's new album, Big Dog Daddy.

Now Pinson is back with the self-produced and wistfully titled Songs for Somebody on his own label, Cash Daddy Records. The album cover shows him leaning against his beloved 1963 International pickup truck, its bed stacked with boxes of CDs and a statue of Jesus on the dashboard.

Like its predecessor, Songs for Somebody bristles with images of Pinson's Texas boyhood: bars, endless roads, high school football games, willing girls, booze-bonded buddies, disapproving parents and the relentless shadow of a demanding God.

"Past Comin' Back" is one of the most vivid and visceral get-out-of-town songs ever written. It is so onomatopoetic that you can hear the car revving. "If I Don't Make It Back," while set in a wartime frame of reference, explores the whole realm of friendship and keeping heartfelt promises. "Back in My Drinkin' Days" contrasts transitory fun with enduing pleasures. "Just to Prove I Could" catalogs the foolish and self-destructive moves a boy will make to establish his own identity.

Although personal agonies abound in Pinson's music, he is quick to point out that he is, after all, writing songs and not autobiography.

"Everybody's tormented at some time," he observes. "I tend to wallow in it a little bit to get songs. Sometimes it's other people's torment. It's not all firsthand. But I occasionally put it on my shoulders. I wear other people's pain like it's my coat.

"The irony is that I came up in a pretty straitlaced household. I didn't do a lot of drinking or anything coming up in school. But when I got to Nashville -- Nashville's kind of a drinking town [and] that's the CMA understatement of the year right there -- I kind started making some noise for myself. I was never an alcoholic or anything. I never did drug number one. Ever. But in between dating girls that I shouldn't have and creating noise just to pass the time, I came in contact with a lot of stuff and sponged it up. Then when [I] put it on a record and people [wore] it around for two years, it became this thing of, 'What a tormented man!'"

Growing up, Pinson's main artistic inspiration was the poetry of Shel Silverstein. Oddly enough, he never studied Silverstein's song, many of which -- "A Boy Named Sue," "One's on the Way," "Marie Laveau" -- were country hits.

"My mom was a teacher," says Pinson, "so I knew [Silverstein's book] The Giving Tree, the poetry. That was my first influence. This was before music really influenced my life. I grew up in a little town where there wasn't a lot of radio. My dad was a football coach who taught me three [guitar] chords that he'd picked up in Vietnam. Then there were Willie Nelson, Johnny Cash and Don Williams [records] in my house. And that was about it.

"I knew at an early age I was a storyteller, just from reading poems. I could make them funny where they were supposed to be funny. I could pause and milk them. I competed in [storytelling] as a school kid. So I knew it was my knack to communicate. I just didn't know in what capacity."

After high school, Pinson joined the Army. While he was stationed on the West Coast, he attended a songwriters' conference at which he met Nashville composers Larry Boone and Paul Nelson. They were sufficiently impressed with Pinson's work to give him their numbers and encourage him to keep in touch.

"I moved to town [in 1996]," he says, "and they watched me starve for about three years."

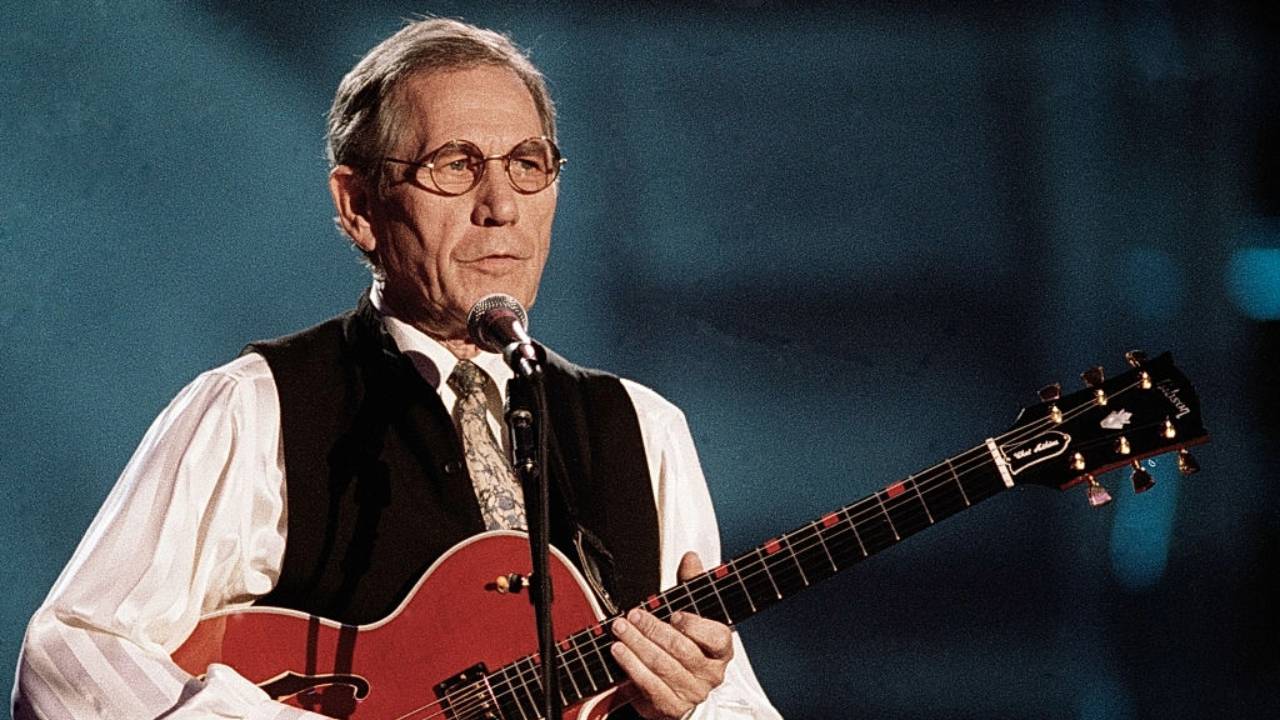

Eventually, Pinson signed a songwriting deal. In 2000, Tracy Lawrence gave the newcomer his first commercial boost by recording "Unforgiven," a song Pinson co-wrote with Boone and Nelson.

Distinctive as his songs are in both theme and imagery, Pinson says it hasn't been difficult to find congenial co-writers. On Songs for Somebody, his lyrical collaborators include Liz Rose, Jim Collins, Tim Nichols, Daniel DeMay, Joe Doyle, Scooter Carusoe, Jon Randall, Luke Bryan, Billy Joe Walker and Brett James.

Picking a writing partner, Pinson explains, "is just [a question of] who do you get along with, who do you not have to explain yourself to. ... Mostly it's people who 'speak Bobby' and will just let me be wrong ... people who aren't going to make me have to explain how come I've got seven of the same rhymes all in a row for alliteration."

The separation from RCA was wrenching, Pinson admits, but he's grown philosophical about it: "It just wasn't supposed to be," he concludes, "and I couldn't figure out why until I realized that I just had to stop trying to figure out why. I found a lot of peace with that."

Pinson's turn at RCA and the exposure that came from the relative success of "Don't Ask Me How I Know" gave him the will and the wherewithal to chance the new album. His absence from the music scene has also created a mystique, he says, that is helping him get better concert bookings.

"When I had the record deal, I was doing a bunch of free radio shows and working a lot --- but basically making my band money," he says. "I wasn't making anything as the artist. It was when I disappeared that everybody had to come find me. It's always better when they find you."