Amy LaVere: Breathy, Bemused and Bereft of Regret

From the Oxford American Music Issue 2007

In the song "50 Ways to Leave Your Lover," Paul Simon presents gutless exit strategies straight out of the Bush administration playbook (don't need to discuss, get a new plan, etc.); but Amy LaVere has a better solution for getting out of a bad situation.

"Killing Him," the first track on LaVere's new Anchors & Anvils, features a woman accused of stabbing her man. It's a squalid story, but the woman's realization that "killing him didn't make the love go away" makes the song both evocative and haunting.

She thought of him every night and all of the day

Missing her baby she did away

Blowing kisses through the concrete sky

Hoping they'd reach him in heaven high

Bob Fergo's violin adds a funereal touch and the song's sadness is punctuated by LaVere's acoustic bass playing, which chugs along like a reluctant heartbeat.

One can imagine the words drifting out of a doomed mountain valley stuck on the wrong side of the twentieth century. But LaVere's matter-of-fact delivery is breathy, bemused, and bereft of regret. Only when she stretches the final syllables of "six by eight room," does she croon the way you'd expect from a woman-done-wrong song. While not all the tracks on Anchors & Anvils are this bleak, most touch on failed relationships and that desperate middle ground between the prelude to the break-up and the realization that it's over.

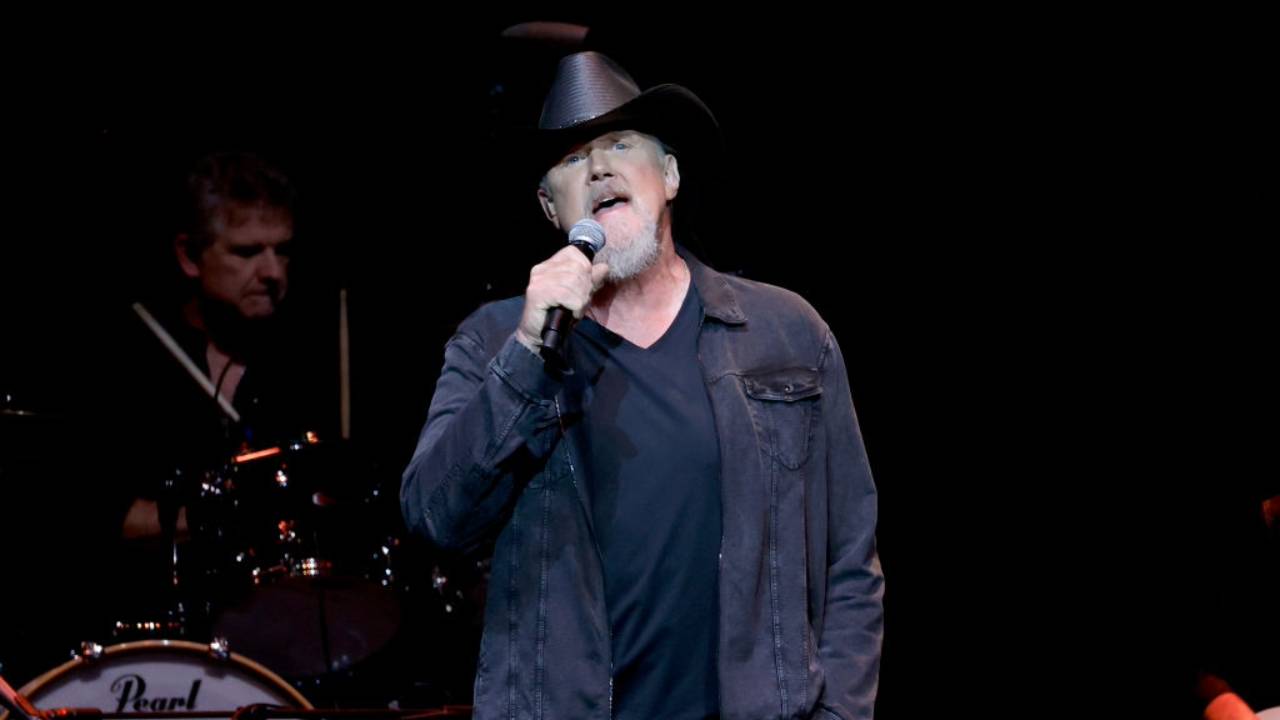

LaVere takes the stage at Pappy & Harriett's Pioneertown Palace, a roadhouse in the California high desert about one hundred and twenty miles east of Hollywood. The jagged mountains and bizarre Yucca trees feel both alien and familiar. Pioneertown was founded in the '40s for the purpose of filming Westerns and its craggy peaks and dusty mesas can be seen in hundreds of commercials, TV shows, and films. Today, Pioneertown gets by on overpriced kitsch. Walking down Mane (sic) Street, one expects cowboys to come barreling through the swinging doors.

It is early summer, which means triple-digit heat during the day and surprisingly cold nights. Desert kooks, Joshua Tree climbers, weekend bikers, and sun-staggered Angelenos in rockabilly attire suck down margaritas and tear into Santa Maria-style barbecue pork ribs.

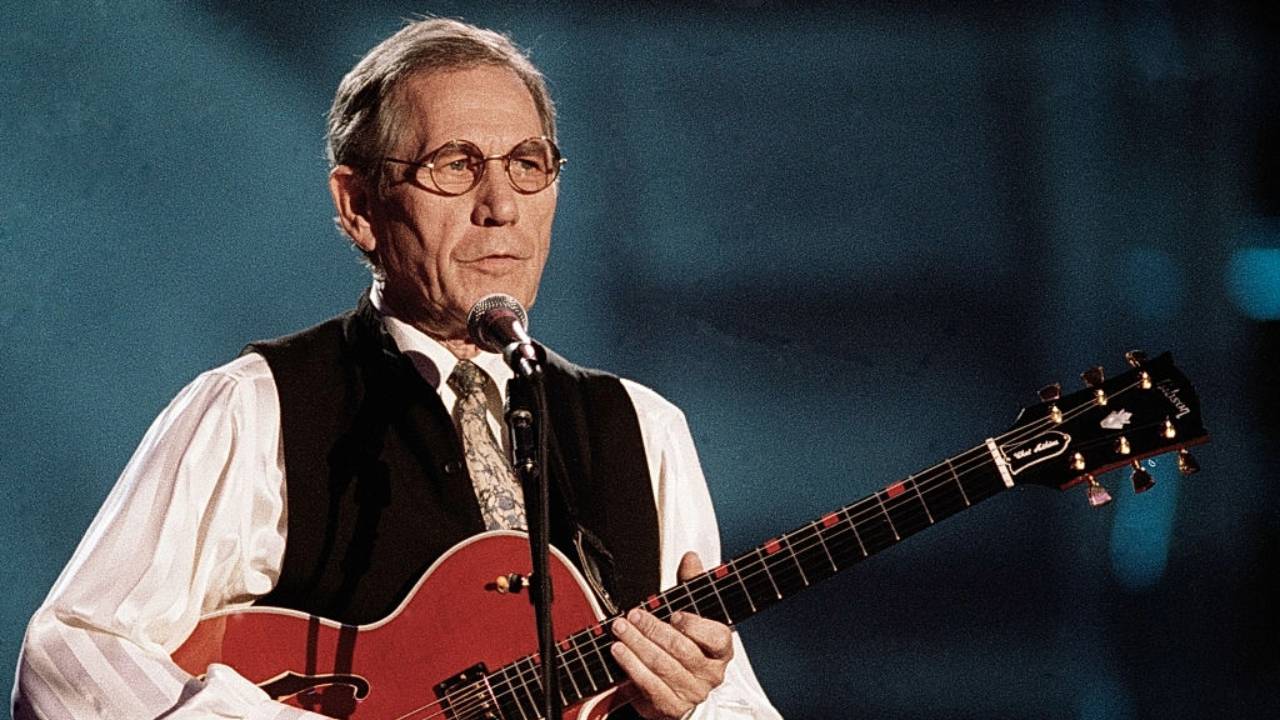

Amy LaVere bears an uncanny resemblance to Judy Garland. Wearing a slip of a dress with a flowered print, LaVere appears both wholesome and glamorous. Even in heels, her upright bass stands taller than she does. At her feet, a shot of bourbon anchors a set list torn from a spiral-bound notebook to the stage. Her voice is soft, her manner timid as she addresses the raucous crowd, but from the moment she starts playing the '70s-model Engelhardt bass that once belonged to Dave Roe, who played with Johnny Cash, the audience is utterly hers.

Born in Shreveport, LaVere lived her first years in Bethany, a town on the Texas/ Louisiana border. As a child, she listened to Dolly Parton and Linda Ronstadt, but Willie Nelson was her father's favorite. Her father was an iron worker and, in her seventh year, he got a job with General Motors forcing the family to hit the road. Thirteen schools later, LaVere ended up at a tiny little town approximately forty minutes north of Detroit, where she fronted an aggressive art-rock band called Last Minute. When she was twenty-one, she moved to Nashville to work as a receptionist in a music-management office. In Music City, she got married and unmarried, and now lives in Memphis, where she works as a tour guide at Sun Records. Sometimes LaVere gets asked to do session work in the Sun studios late at night after all the guests are gone. "That's when you feel it. I do. Whatever magic is there."

But how do you classify LaVere's music? Behind Patsy Cline in the classic-country category? In front of Lucinda Williams in the altcountry section? Alongside Django Reinhardt in the gypsy-jazz bin? Is there even such a thing as a gypsy-jazz section?

It's a conundrum LaVere's aware of. "I think the hardest part for most artists," she confesses, "is honing in on one thing." LaVere's ability to hone in on her characters gives her music universal appeal. In their obsessive attention to detail-a dusty lamp, dripping faucets, unfinished laundry-her songs resemble accomplished works of fiction. Perhaps it's the tour guide in LaVere, pointing out the breakdowns and bust-ups of life in a pleasantly modulated voice. She wants us to accept that places are imbued with the narratives of those things that inhabit them. The geegaws we collect during the course of a relationship may be worthless, but they become meaningful over time. But what are to make of all this junk when the love goes away?

In "Washing Machine," LaVere sings of a trapped housewife planning her escape:

Sitting in the kitchen at night

She'd listen to the washing machine

Wishing that she could leave

But there were so many loads to clean

It's a dilemma lovers with one eye on the door face every day: I gotta get out of here, but who'd pick up the kids, walk the dog, water the plants?

The title Anchors & Anvils comes from a line in "Overcome," in which a woman drowns in everyday detritus. The song was written the day LaVere moved out of a house she loved -- a quintessential LaVere situation: romanticizing the place while despairing over what keeps her there. Yet there's also a carnivalesque mood in "Overcome" that's both enticing and oddly menacing. Listening to the song is like turning the crank on a jack-in-the box that never pops.

"On the stage you're much freer to express all the things that you like," LaVere says. She woos the crowd at Pappy & Harriett's with stories about getting her hair done earlier in the day or drinking bourbon during a hurricane, stories that are considerably lighter than the ones she tells in her songs.

During "Pointless Drinking," easily the saddest song on the new record in a hurts-like-a-rock-in-my-shoe-but-every-step-brings-me-closer-to-you kind of way, she makes the audience laugh. The song was written by the drummer Paul Taylor who also produced LaVere's excellent first album, This World Is Not My Home. Humor lies dormant in many of LaVere's recordings, waiting to be resurrected with a knowing smile that lets everyone in on the joke. Sure, the punchline may be heartbreaking, but it's still funny.

On "Never Been Sadder," a track from her previous album, LaVere turns the song on its ear with a coquettish twirl of her hand as she sings, "I tried to be good, as good as I could be." Here the audience gets a glimpse of Amy LaVere the actress. The woman who won the part of Wanda Jackson in the Johnny Cash biopic Walk the Line (her role was cut from the movie) as well as a part in Craig Brewer's Black Snake Moan. Her gesture is part renunciation (I didn't try that hard) and part resignation (I'm no good at being good) and it makes LaVere seem both knowing and knowable, easily within reach and yet out of our league. LaVere doesn't write in-love-with-being-in-love songs. Her lyrics resonate with a hard-won truth. Anchors & Anvils may be music to leave your lover to, but you better watch your back.