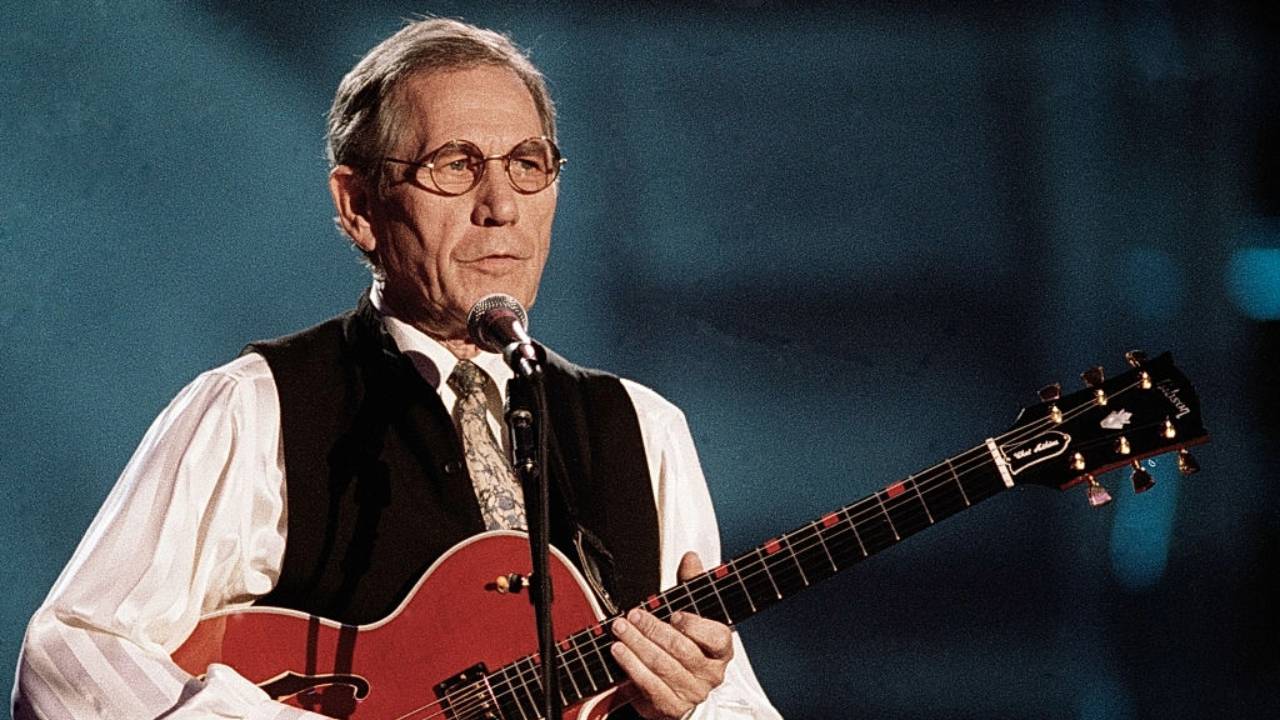

Mel Tillis Finds a Home on 'Billboard''s Comedy Chart

During a lengthy and distinguished career, Mel Tillis' recordings have spent a lot of time in the Top 10, but it wasn't until recently that he faced competition from Dane Cook, Weird Al Yankovic, Lewis Black and Flight of the Conchords. That's because his You Ain't Gonna Believe This ... is currently spending its 11th week in the upper reaches of Billboard's comedy albums chart.

Tillis had already made his mark as a singer and songwriter long before mainstream America was introduced to his storytelling and comedic timing in the '70s when he was an A-list guest on major TV talk and variety shows. In light of that, it's hard to believe he was more than 50 years into his career before he released a comedy album.

You Ain't Gonna Believe This ... contains 19 of his humorous stories and three songs. The comedy routines, punctuated by the stuttering delivery he's so famous for, were recorded live during the 13 years he performed at his theater in Branson, Mo.

"I taped every show, so my new CD is stories from the stage live," he said during an interview with CMT.com. "I've had a wonderful career. I've been blessed in every way you can."

Those blessings include several No. 1 singles as an artist, including "I Ain't Never," "Good Woman Blues," "Heart Healer," "I Believe in You" and "Coca Cola Cowboy." He's written more than 1,000 songs, including classics such as Bobby Bare's "Detroit City," Ray Price's "Burning Memories," Ricky Skaggs' "Honey (Open That Door)" and Kenny Rogers & the First Edition's "Ruby, Don't Take Your Love to Town."

After gaining national TV exposure as a semi-regular on The Glen Campbell Goodtime Hour in the '70s, film roles came his way such as Clint Eastwood's Every Which Way but Loose, Burt Reynolds' Smokey and the Bandit II and W.W. & the Dixie Dancekings, not to mention Cannonball Run and its sequel.

Whether you're having a conversation with him or watching him onstage, though, one of Tillis' greatest blessings has to be the energy he still exudes at age 78. His sense of humor is as sharp as ever, and he continues to maintain an active touring schedule with his longtime band, the Statesiders.

No doubt, Toby Keith sensed Tillis' youthful outlook when he asked to release the comedy album on his Show Dog-Universal label. Like so many opportunities in Tillis' life, it wasn't a calculated plan.

"I know Toby, and I went out to Norman, Okla., and he came over to the show," he said. "He was on the bus. I gave him a copy of the demos of it. He took it home. The next thing I knew, he said, 'Hell, I want you on Show Dog.' That's how it happened."

Tillis' good luck is underscored by talent and hard work, but he stumbled into his entertainment career while working as a fireman for the railroad in his home state of Florida.

"I'd use my railroad pass to come to Nashville," he explained. "The first time I was here, they only had three publishing companies -- Acuff-Rose, the oldest, Cedarwood was next, then Tree. I signed with Tree Publishing, and I became a writer. I had no idea that I could write a song."

Of course, Tillis probably didn't think he was very lucky when he first sought the approval of Acuff-Rose chief Wesley Rose, the songwriter and music publisher who enjoyed some of his greatest successes with Hank Williams.

"I went up to Wesley Rose's office," Tillis recalled. "He liked my singing, but he said, 'Man, we don't need stuttering singers. We need copyrights.' I said, 'Sir?' He said, 'Songs. We need songs.'"

Tillis returned to Florida, wrote some initial songs and returned to Nashville, managing to get the attention of Buddy Killen at Tree Publishing.

"Buddy Killen took one of them called 'Five Feet of Lovin' ' and got it on the back of 'Be-Bop-a-Lula' for Gene Vincent. So I'm on the back of a million-seller. I quit the railroad and I wrote several other songs."

After signing with Tree -- and then getting out of the contract -- Tillis became a writer with Cedarwood Music Publishing, a company partially owned by honky-tonk legend Webb Pierce. He also signed an artist deal with Columbia Records.

"I had written a song called 'Honky-Tonk Song,'" Tillis said. "It was my first record on Columbia, and it got covered by Webb Pierce. It killed my record. Before that, though, I'd written song called 'I'm Tired.' Ray Price came to Tampa, and I went out to see him and played him that song."

It was around that time that Tillis began understanding the business side of songwriting and publishing.

"I had a manager," he said. "He got a third of the song, I got a third of it, Ray got a third of it. Backstage at the Opry, he was singing that song. Webb heard it and said, 'I kind of like that, lad.' He told that to Ray Price. He called everybody lad, Webb did.

"He said, 'I'd like to record that.' Ray said, 'No, I'm gonna cut this.' Webb said, 'Hell, you don't need it. You've got "Crazy Arms" that's been in the damn chart at No. 1 for 30 weeks.'"

After the encounter, Pierce remembered the first verse of "I'm Tired" and sang it songwriter Wayne Walker.

"Wayne wrote two more verses to it, so Webb cut it," Tillis said. "He said, 'The hell with Ray.' And I'm sitting at home in Florida on the bed. I had my radio on, listening to the all-night show with Eddie Hill. He played 'I'm Tired.' It started off with my verse ... but then those other two verses. I jumped up and ran into my mama's bedroom and said, 'Mama, we're gonna be rich! They're singing my song. I think it's my song."

Tillis finally moved to Nashville in 1957 and found success as a recording artist, but he was best known as a songwriter until he became a regular on Porter Wagoner's syndicated television show.

"Porter and I were big friends," he said. "We fished a lot together. I taught him to fish, actually. He'd never been fishing with a rod and reel. I think he'd just done some cane-pole fishing when he was a boy. But I took him up to Center Hill Lake, and we'd fish all night long. He became a great, great fisherman. He'd tell you that, and he could show you. He had them all mounted on his wall.

"One night up at Center Hill, he said, 'You know, Tilly, I'm gonna make you a star. I'm gonna put you on my TV show?' I said, 'You ain't.' He said, 'I am. It's my show and my bus.' The next thing I knew, he was introducing me every week on that show. I was there, I think, for six months. I was there before Dolly Parton, actually.

"Anyway, I was there for six months, and he fired me," he added. "I got in a damn fight at Linebaugh's [a restaurant on Nashville's Lower Broadway], and I wasn't even in it till somebody hit me in the neck. I got under the table. I hid. And here come the cops."

Wagoner, of course, heard about the incident.

"He called me over to his apartment and said, 'Tilly, I'm gonna have to let you go. You're not the kind of person, the way you're doing things, that I think would be good for the show.' I said, 'OK, Porter. Whatever you think.'"

Shortly after their conversation, Tillis' lucky streak kicked in yet again.

"The very next day, I got a call to be a semi-regular on The Glen Campbell Goodtime Hour," he said. "I began to do all the shows after that -- Merv Griffin, Dinah Shore, Johnny Carson."

Tillis' high profile led to the film roles and business ventures that further ensured his longterm financial security. One of those investments was the purchase of Cedarwood, the publishing company that once paid him a weekly salary of $75. He purchased the company in 1983 for almost $3 million and later sold it to Polygram Music. He won't say how much he made from the deal, other than to laugh, "It did pretty good."

Some of his old songs he wrote are still bouncing back.

"It's hard to get a new song cut today," he said. "There's 10,000 damn writers in Nashville, and everybody is out for a piece of this and a piece of that, and it's just so hard. But I got one cut last year that I'd written for the Everly Brothers called 'Stick With Me Baby.'"

When he was told Alison Krauss was recording it, Tillis wasn't sure about her choice for a duet partner -- Led Zeppelin vocalist Robert Plant.

"I said, 'Who the hell is he?'" Tillis laughs. "I'd never heard of him, but they cut it on that album, Raising Sand. And, man, my first royalty check on it was $55,000. My catalog has been so wonderful."

Plant later provided background vocals when Buddy and Julie Miller recorded another Tillis original, "What You Gonna Do Leroy," for their Written in Chalk album. And when Jamey Johnson recorded his latest album, The Guitar Song, one of the songs he chose was Tillis' "Mental Revenge," a hit for Waylon Jennings in 1967.

"Kris Kristofferson and I used to hang around at [songwriter and music publisher] Marijohn Wilkin's cabin in the woods and write songs," Tillis said. "Man, we loved Bob Dylan. We'd listen to his songs and think, 'Boy, I wish I could write one like that.' I wrote 'Mental Revenge,' but I did it as a waltz. I cut it like that. Later on, Waylon did it and changed it."

Like most people who become members of the Country Music Hall of Fame or receive the Academy of Country Music's Pioneer Award, Tillis says singers, songwriters and musicians never realize they're achieving anything of importance while they're in the middle of the creative process.

"I don't think you're aware of it," he said. "If you were, it probably wouldn't be as good. ... I'd always got extremely nervous before I wrote a song. And then when I did, I'd write three or four. And it just seemed like they were all gifts, man. Everywhere I looked, God almighty, here comes 'Ruby, Don't Take Your Love to Town,' 'Detroit City.' They were just coming from everywhere."

These days, Tillis spends his much of his time painting and working on a novel, but he hasn't abandoned songwriting. Or his sense of humor.

"I do a little bit of writing," he smiled. "I started one the other night called 'She's a Bear in the Morning but a Pussycat at Night.'"