NASHVILLE SKYLINE: Nashville Dreaming With Dierks Bentley and Del McCoury

(NASHVILLE SKYLINE is a column by CMT/CMT.com Editorial Director Chet Flippo.)

So, I'm gazing out my office window down at the Ryman Auditorium, where a crowd is growing around a new outdoor stage set up in front of the Ryman. It's a beautiful, balmy, sun-splashed fall afternoon, the sort of lazy day that makes you remember why you love living in Nashville.

Downtown Nashville is full of people just strolling around enjoying the weather. I can see some of them dropping into the many honky-tonks on Lower Broad, where they can sample some afternoon brews and live country music. I can just about smell the tangy aromas rising from the barbecue ribs and sausage and brisket slowly smoking in the big cast-iron ovens down at Jack's Bar-B-Que, just across the alley from the Ryman.

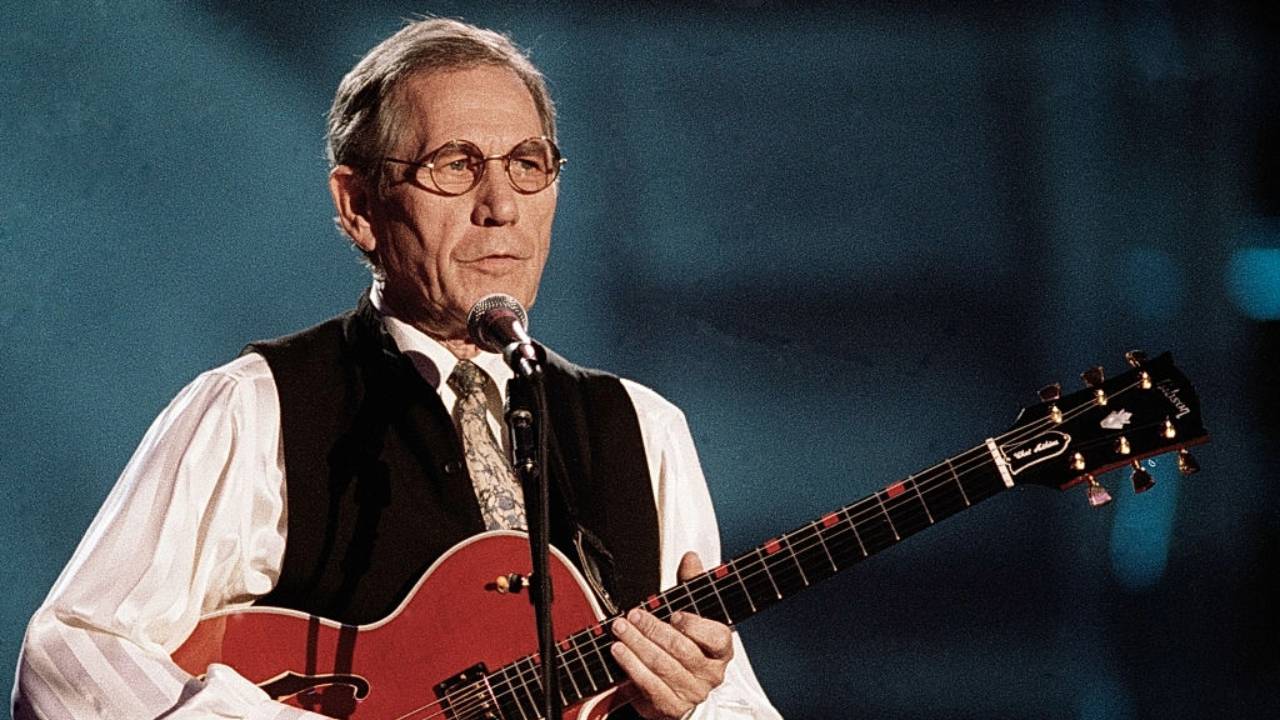

And another reason for loving living here is the purpose of that temporary stage out front of the Ryman. In a few minutes, Del McCoury and his McCoury Band will be joined by the likes of Vince Gill and Dierks Bentley and Sam Bush for a robust and rousing and sometimes reverent set of songs.

And it's a free show. It's marking the beginning of bluegrass week in Nashville, where the IBMA (the International Bluegrass Music Association) is holding its annual conference. So there are a lot of bluegrassniks out on the streets, and there will be much live music for days to come.

One big reason to celebrate bluegrass week is the fact that this year marks the late Bill Monroe's 100th birthday. It's appropriate that McCoury's show is taking place in the shadow of Ryman. It was on that Ryman stage in 1946 that Monroe first unveiled the definitive bluegrass band when he added Earl Scruggs and his three-fingered banjo-picking style to his lineup of mandolin, fiddle, guitar and acoustic bass.

It's another example of the big top tent that is country music. It still works. Artists of almost every stripe are welcomed in to the tent -- at least for a tryout. Those that fit in, well, they can stay. The ones that grate against the nerves and demand 24-hour manicurists and throw tantrums and ignore the fans -- well, hit the road, Jack. You are done here.

This night, Vince Gill will go onstage at the Grand Ole Opry to announce to Rascal Flatts that they are being invited to join the Grand Ole Opry. Flatts could not be more different from Del McCoury. But it all fits. Sure seems like everybody is welcome.

They used to come in on the Long Dog. The Greyhound bus, that is. All those young and hungry-looking singer-songwriters with a battered guitar case and a severe case of the hungries for making it in country music.

Now you'll see their new versions flying into BNA airport with a manager or investor in tow. They can no longer travel the Kris Kristofferson route, living in a rooming house and working as a janitor at Columbia Records to try to get a shot with one of his songs. Now it's big business. There is no bottom to start at any more. There's only success or failure.

BNA sees everyone jetting in, from those new-age wannabes to refugees from other music genres seeking a country shot in the arm. Bret Michaels wants to test the country waters? Sure, Bret, give it a try. It may spit you back out, but why not take a shot. Sheryl Crow? She's got deep country roots. Kid Rock? He's more bone-country than many of the pretty young male models posing as country stars these days.

Country music has truly become the Alcoholics Anonymous of popular music, where people figuratively get up at quasi-AA meetings and announce, "Hello. My name is XYZ. I am a country music lover." And out of the closet they come. Are they just faking it? The country fans will make the ultimate judgment. And the fans are seldom wrong.

Sometimes when all the commercialism of the business -- and it is very much a business, a very big business -- it's easy to forget what drew you to the music in the first place.

Simply put, it's the purity of much of the music. Del McCoury's music is pure, plain and simple. It's not purist music, not bluegrass purist snob music. He still performs a lively version of the Lovin' Spoonful's "Nashville Cats." But he also preserves the music of the elders. It's true generational music -- music that will endure. He learned much when he was the lead singer for Bill Monroe and the Bluegrass Boys, and to mark what would have been the Father of Bluegrass's 100th birthday this year, Del is releasing Old Memories -- the Songs of Bill Monroe this fall.

Dierks Bentley, who has frequently collaborated with Del in the past and views him as a mentor, left the McCoury live show outside the Ryman for an observance of his own -- a No. 1 party for his song "Am I the Only One." Del himself will likely never have a No. 1 party at BMI or ASCAP for charting a No. 1 song -- because country radio will not touch bluegrass. Nor probably should it. Bluegrass is close-to-the-ground music. It -- or its string band ancestry -- is actually the first house music. For it was in people's houses and yards that the music found its first expression.

Sometimes an idyllic afternoon such as this can lead to idle reflections and random memories coming back. Listening to Del, I am reminded of a brilliant young singer-songwriter, who could have been, I guess, another sort of Kris Kristofferson. Or Dierks Bentley or any other country star of recent years. His name was Bobby Charles. He was a naïf -- a true innocent from rural Louisiana, who wrote the early rock 'n' roll anthem "See You Later, Alligator," which as recorded by Bill Haley & the Comets was a shot across the bow of conventional music. He also wrote "Walking to New Orleans" for Fats Domino, among many other songs. His "Tennessee Blues" remains a true classic.

Charles moved to Nashville to join the progressive singer-songwriter scene here but -- in those days when longhaired songwriters were watched with suspicion -- was busted by Nashville police for marijuana possession. From what I hear, he panicked, jumped bail and fled to Woodstock N.Y., where he showed up barefoot and in bib overalls -- thinking no one would recognize him. Bob Dylan's manager, Albert Grossman, believed in him and quashed Charles' Nashville police problems and tried to put him out on the road with The Band. Didn't work out, and Charles ultimately disappeared back into the swamps of Louisiana, where he died in 2010.

He could have been a contender. Maybe he should have stayed in Nashville. He might have seen some sunny afternoons of his own at the Ryman. There are a lot of stories in this town.