NASHVILLE SKYLINE: Earl Scruggs: A Quiet Bluegrass Giant Is Gone

(NASHVILLE SKYLINE is a column by CMT/CMT.com Editorial Director Chet Flippo.)

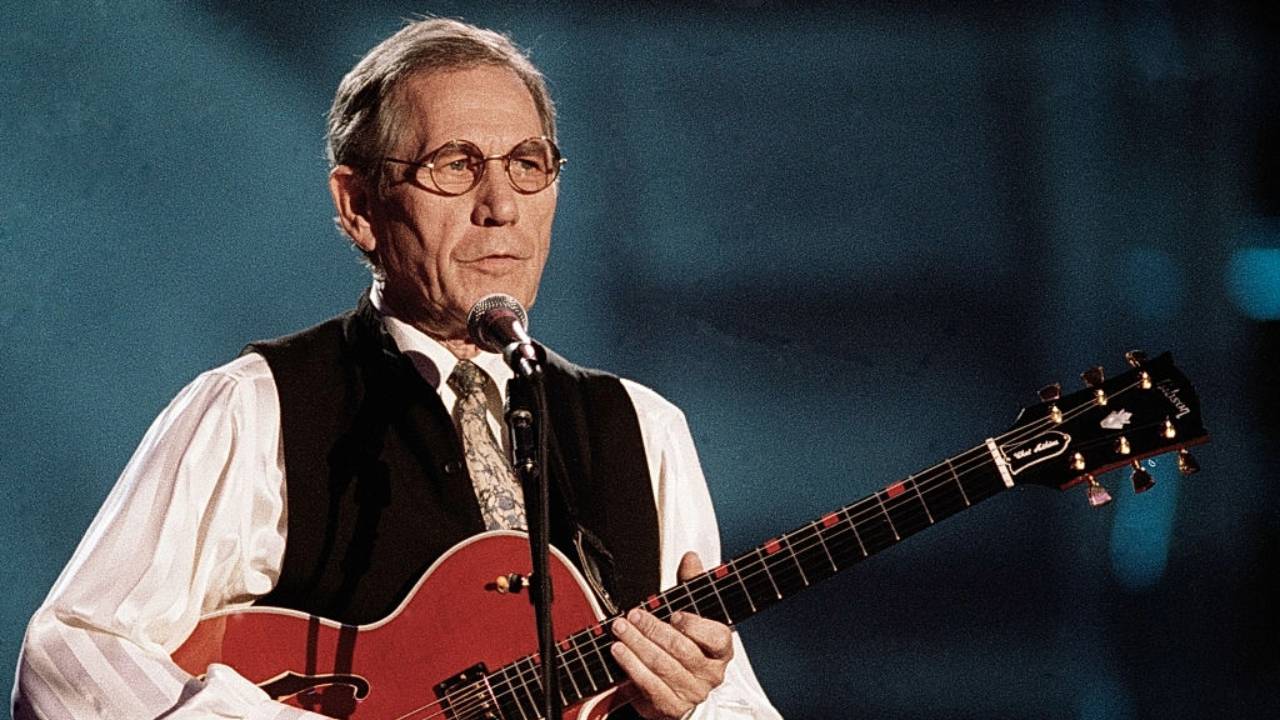

In a unique way, I think the late Earl Scruggs, who passed away Wednesday (March 28) at age 88, was both a calming and a transformative/transforming force in Nashville's emerging music culture from the late 1940s on.

For traditional music, Earl's dynamic three-finger picking style propelled both the banjo and bluegrass onto the national stage. He made Bill Monroe's Blue Grass Boys into a popular music force. He got the music into the movies and onto TV and thus across popular culture at large. He changed the music forever. And he also later moved to meld bluegrass with modern folk-rock and other musical forms.

But as a calming influence, he remained a tranquil bridge between the past and the future. He was a link between the old, traditional world of country and the bright, new, innovative music of the future. He wasn't burning any bridges. He was building them. You never heard him raise his voice. But people always listened to what he had to say.

Earl later broke with Lester Flatt over musical disagreements about music direction. Earl was listening to Bob Dylan and other new forces and sensed and heard the changes in music culture and wanted to be a part of that. Lester felt the old ways were the best. Why change?

As his friends knew, Earl was always quiet and never forceful, but he projected a sense of dignity. He certainly knew his worth and his place in history. Once, at a bluegrass festival, the leader of a certain lesser-known bluegrass group which shall go unnamed here, approached Earl backstage. He slapped Earl on the back (which you didn't do) and said something to the effect of, "Earl! So good to see you! You know, our banjo player is sick today, so ... ."

Earl cut him off with the words, "Is that right?" And turned and walked away. There would be no fill-in gigs with second or third-level bands for Earl Scruggs.

After Flatt & Scruggs split, Earl grew his hair to a respectable length, just long enough to be disrespectful by the current bluegrass styles then. And he formed a progressive country band with his talented sons Gary and Randy. As the Earl Scruggs Revue, they toured far and wide and continued with musical experimentation.

I first got to know him at the 1971 recording sessions for the Nitty Gritty Dirt Band's first Will the Circle Be Unbroken album. That record was a major bridge spanning the Nashville generations, and I'm not sure many people understood that at the time.

I certainly didn't at first. I was a longhaired writer from Rolling Stone magazine dropping into Nashville. But I was also a country music lover from Texas who had been to many bluegrass festivals in East Texas and knew and loved the music and knew who its many players were. I sensed that Earl accepted me after a little while with me and so did the supposedly hippie-hating Roy Acuff. The great Doc Watson couldn't see me, so he did didn't pass judgment on my appearance. Just on what I said. And I apparently passed his test.

What great recording sessions those were, in East Nashville at Woodland Sound. The Nitty Gritties with Acuff, Watson, Scruggs, the matriarch Mother Maybelle Carter, the great bluegrass maverick Jimmy Martin, the wonderful fiddler Vassar Clements, eclectic musician Norman Blake and West Coast country wizard Merle Travis. Bill Monroe looked down his nose and refused to play on the record. But Earl Scruggs showed up and very strongly influenced the bluegrass sound of that still-impressive three-album set. That set should go into the Smithsonian some day. That I got to sing background vocals on the title track "Will the Circle Be Unbroken," of course, will remain the highlight of my musical career. And Earl Scruggs treated me as an equal. When he didn't have to.

I remember that in one interview a few years later, I remarked that Earl pronounced "banjo" as "banja." The next time I saw him he gently reprimanded me. "Chet, I don't say 'banja.'"

"Your're right, Earl. I'm sorry," I said. And that was that. But he kept on saying "banja."

I was fortunate enough to be invited to some of Earl's informal little musical get-togethers at his house on Franklin Road in Nashville. They were very low-key but joyous sing-outs and storytelling by people such as Mac Wiseman and WSM-AM/Nashville DJ Eddie Stubbs.

I'm not sure enough tribute has been made to Earl's late wife, Louise. I'm not sure he would ever have made it anywhere without her. That may be oversimplifying things, but I don't think so. But as the first female manager of a country band (as far as I can tell), she was enormously influential. She was just as soft-spoken yet forceful as was Earl. She never employed a press agent or publicist to hype her. She just did her job.

She transformed the whole concept and treatment of music album cover art when she commissioned the artist Thomas Allen, who had worked with jazz artists, to paint Flatt & Scruggs for their record album covers. His results were so striking that they caused a re-evaluation of what record albums should look like. The painterly results looked nothing like the usual Nashville quickie photos were in those days. The results actually went into art galleries.

I'm glad Earl will have a proper send-off with a full-fledged funeral service at the Ryman Auditorium on Sunday (April 1). That's a proper launch to glory for a true music star.