Scott Hendricks Develops Talent Across the Decades

Scott Hendricks arrived in Nashville in 1978 to a music community that was headed straight toward the Urban Cowboy era. In the midst of that changing scene, Hendricks earned a reputation first as an engineer and then as an independent producer with an ear for new talent, due to his work with the harmony-driven, pop-influenced group Restless Heart.

Now almost 35 years after making that move from his native Oklahoma, Hendricks remains one of the city's most notable producers, thanks to chart-topping hits in the 1980s, 1990s and 2000s -- most recently with Blake Shelton and Hunter Hayes. He also produced breakthrough albums for Brooks & Dunn, Faith Hill and Alan Jackson, among many other fan favorites.

Although he's still producing, Hendricks also serves as the senior vice president of A&R at Warner Music Nashville, following similar positions at Capitol Nashville and Virgin Nashville.

A few days after his label team threw a celebration in honor of 50 No. 1 hits he has produced across a variety of country charts, Hendricks called in to CMT.com to discuss his earliest success, his theory about emerging talent and his biggest wish for country radio.

CMT: You had numerous No. 1 hits with Restless Heart, one of the most prominent bands in the 1980s. What set those guys apart in that era?

Hendricks: They sounded different, and most of the acts that I've had success with, I can say the same about them. They had a different sound than what was happening at the time. With Restless Heart, I can remember working on that record before we even had a record deal. We were thinking the whole time, "Wow, this is really progressive for what's happening out there. I'm not sure if anybody will like this, other than those of us who are making this right now." But we loved what we were doing. I didn't know if anybody was going to buy into it or not, but it sure was fun to make.

You came onboard early in their career, as well as the careers of Alan Jackson, Brooks & Dunn and Faith Hill. Rather than trying to work with established artists of that era, what was so appealing about investing in the new talent?

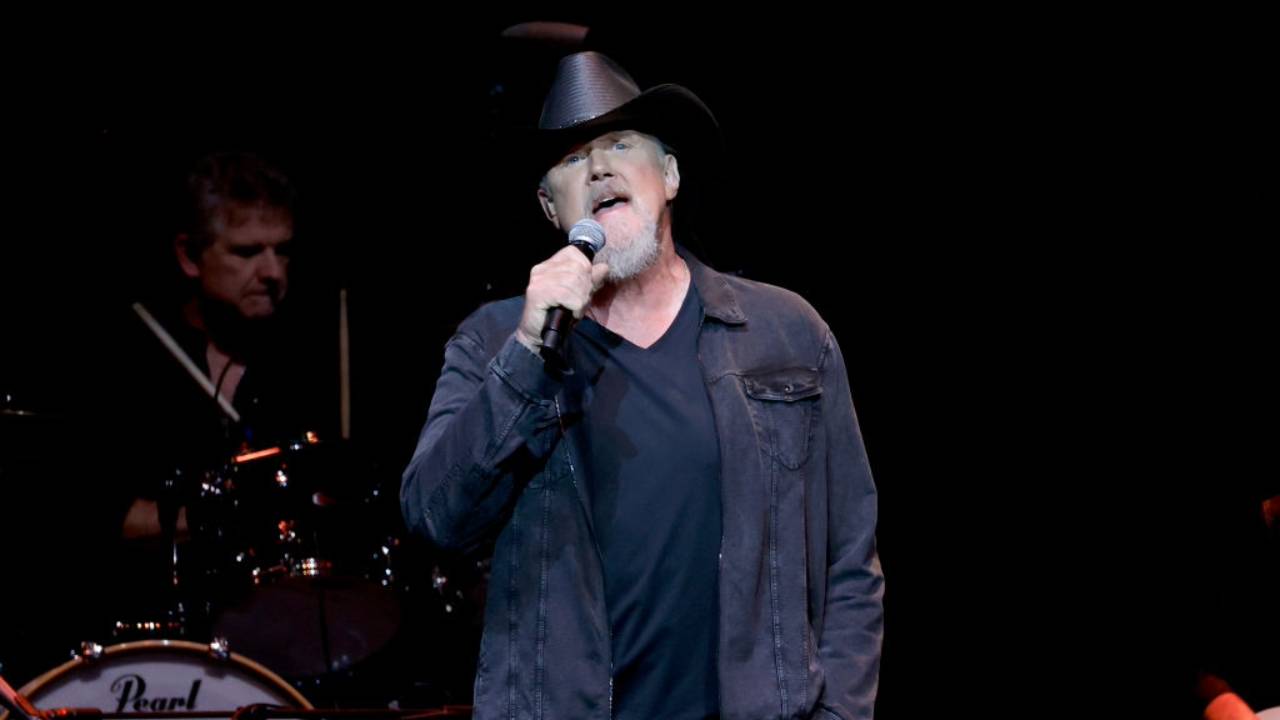

Most of my career has been about finding and signing talent. I've had a couple of situations where I've come onboard after there's been a release prior to me coming on and helping with the direction. John Michael Montgomery is one. He'd had a hit before I came onboard, as did Blake Shelton. But most of the time, like with Trace Adkins and the rest of them, my whole thing has been finding people. ... There is something challenging and fun about creating something that is new to the world.

I would imagine it would be easy to form them into whatever you'd like, but as a producer, it seems like you were able to save what made them special in the first place.

Every one of them was totally different. I brought Ronnie Dunn to Tim DuBois at Arista, who eventually hooked him up with Kix [Brooks]. Ronnie had three songs on a cassette tape that I gave to Tim -- "Boot Scootin' Boogie," "Neon Moon" and "She Used to Be Mine." Those were three No. 1 songs. It's kind of hard to screw that up! But the "Boot Scootin' Boogie" that everybody heard was the third time I had recorded that song. Once with Ronnie [as a solo artist], and once with Asleep at the Wheel. And with somebody like Alan Jackson, Ronnie Dunn and Kix Brooks, those guys are extraordinary writers and they create their direction. In those cases, it's not incumbent on me to find their directions. It's to find their songs.

I remember when Alan Jackson started out, he was writing and recording traditional country music at a time when that wasn't as common.

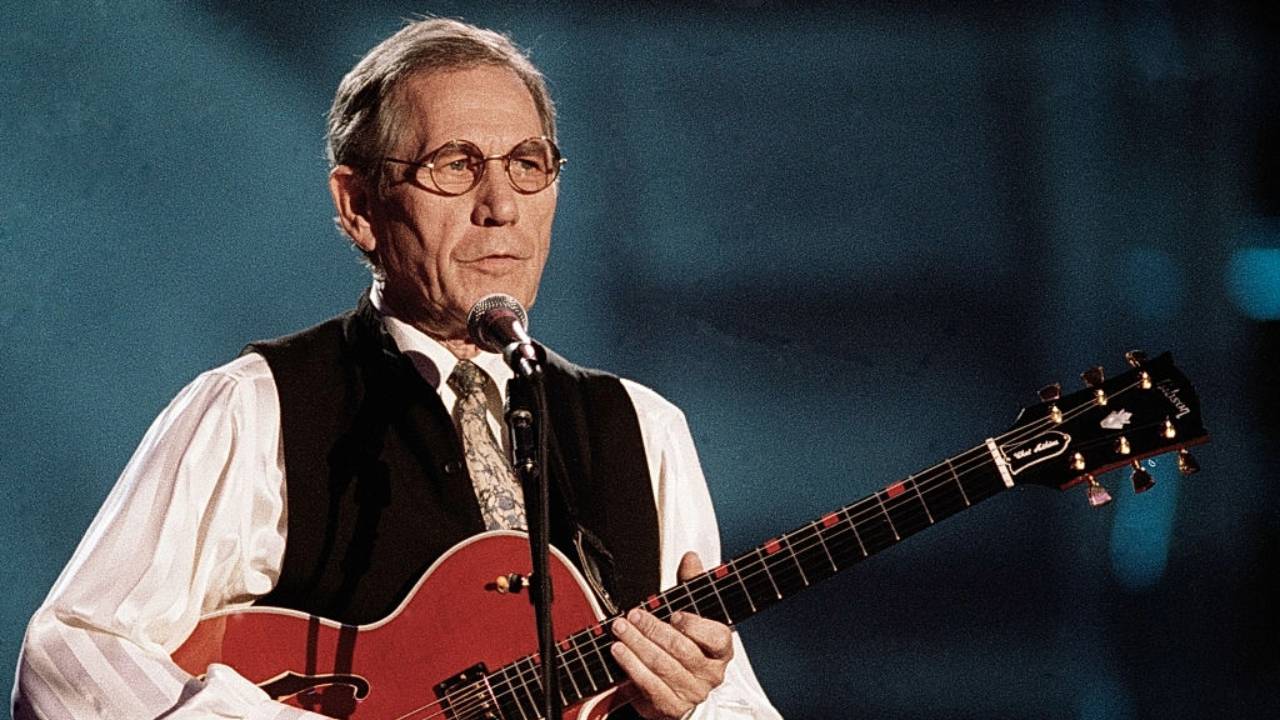

I have a theory: You can't deny talent for too long. It reminds me of Vince Gill. Vince had seven years of making albums before he had a hit. I don't know in this day and time if Vince could have survived. That's one huge difference between now and then. Back then, thank goodness, that happened. It's sad that there are artists today who are super-talented but never get the chance [to develop]. If you don't hit soon in this world, you're not going to be around long.

What were you focusing on career-wise about 10 years ago?

I had been the president of Capitol, then went to open Virgin Records. We were open two years and three months, which is not enough time to establish a new label. We had a gold record on Chris Cagle. In today's world, that would've been killer. But in that world, everything was platinum, and the tide had started to turn on music sales at that point. Napster had just come out, and I could see the writing on the wall that this was really going to be devastating on our record sales from here on out. And it came to fruition. So I went back to being an independent [producer]. Trace Adkins asked, "Would you come back and produce me?" So I did, and we had quite a few No. 1's. I was an independent producer for several years before Warner Bros. wanted me to come over and be a part of that team.

Looking back on country music from the 1980s until now, so much has changed, but what do you think has remained the same in country music since that time?

Well, it all begins with a song. I'd start there. It really does. It begins with a song. And that I hope never changes. ... Obviously, radio has changed a lot. I would love to see us get back to the days where songs would move faster. The public has an insatiable desire for whatever's new and next. People are already looking for the iPhone 5S or the iPhone 6, you know? I don't understand why we don't take that same mentality at radio because people want "new." When we were the healthiest -- and when I say "we," I mean us [the record industry] and radio -- was when things moved faster. That single cycle was 16 weeks versus what is today, which is probably 26 weeks or more. That's really changed. I'd love to see it go back.