What Changes Will Nashville Face in 2015?

(Straight From Nashville is a weekly column written by CMT.com managing editor Calvin Gilbert.)

As we enter the new year, my greatest wish is that Nashville will be able to look back on 2015 without regrets. I’m talking about a reflection that will take place 12 months from now.

When 2015 rolls to a close, Nashville will still be standing and, most likely, thriving, but at what cost culturally?

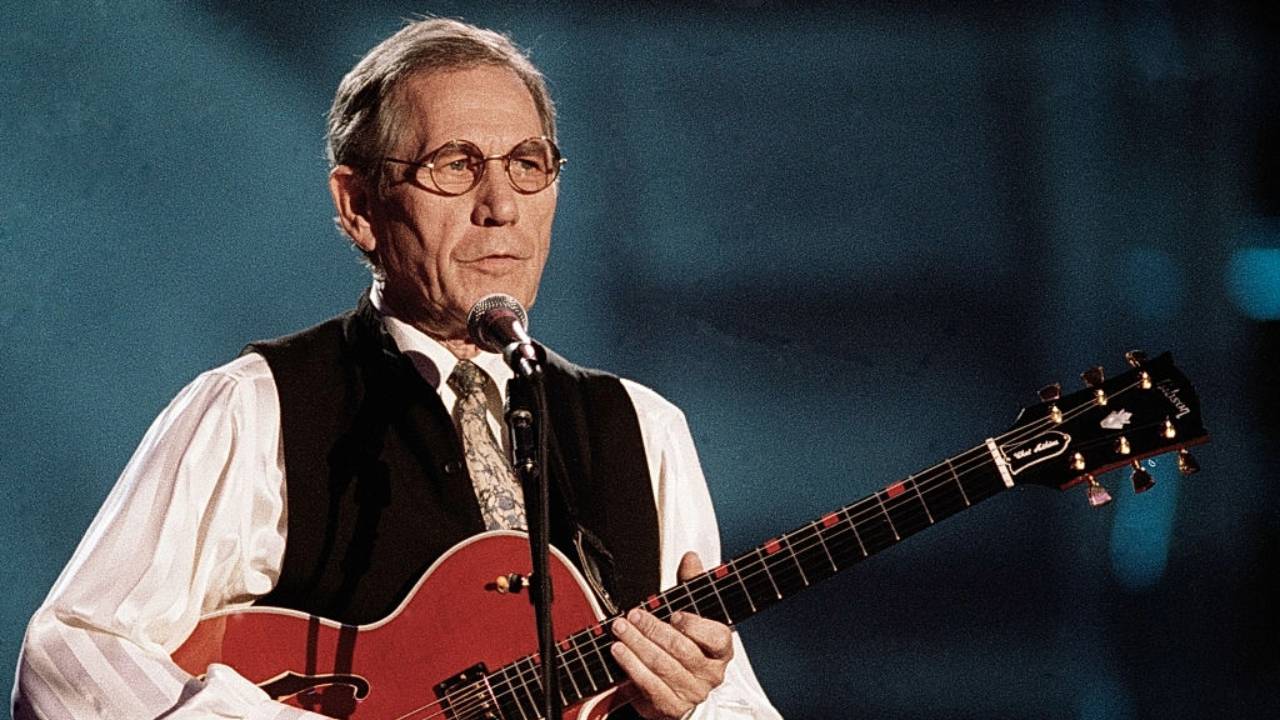

One of the big local stories in Nashville in 2014 involved the future of the RCA Studio A complex on Music Row. Built by three key figures in the development of Nashville’s music industry -- Chet Atkins and brothers Owen and Harold Bradley -- the studio opened in 1965 and has hosted sessions for everyone from Waylon Jennings, Willie Nelson, Dolly Parton, Charley Pride and George Strait to Hunter Hayes and Kacey Musgraves. Others who have recorded there include Tony Bennett, the Beach Boys, the Monkees, Sara Bareilles and Ke$ha.

Rock musician Ben Folds leased the studio in 2002 and operated it as Grand Victor Sound Nashville. For many years, Harold Bradley and the heirs of Owen Bradley and Atkins had been trying to sell the property. Between the decline of the record industry and a soft real estate market on Music Row, it wasn’t easy to find a buyer. That changed in September when Bravo Development bought the property and announced plans to demolish the existing building to provide space for condos and a restaurant.

Music Row is a neighborhood around 16th and 17th avenues that had long been home to record labels, publishing companies and other businesses catering to the music community. There are some modern buildings, but the area’s charm has always been the older houses that now serve as offices. Some of those offices don’t even have signs outside to indicate who works there or what business is being conducted behind the doors.

Almost as soon as I moved to Nashville in 1992, people started telling me the new hot neighborhood was going to be the Gulch, an area just a few blocks from Music Row. At the time, it was a rather isolated, desolate area along the railroad tracks. I remember Tim McGraw and his band playing in a big-top tent there in 2001 to promote his Set This Circus Down album. With the exception of the Station Inn, Nashville’s premiere bluegrass nightclub, there wasn’t much happening in the Gulch, but at least it was easy to find a free parking space.

It took more than a decade for the Gulch to finally transform itself into the hot neighborhood, but when it happened, it happened in a big, big way. And as those high-rise condos and trendy restaurants began to change the landscape between Music Row and downtown Nashville, it only made economic sense for that development to continue to expand into other areas, including Music Row.

Enter Bravo Development and its plan to build condos and a restaurant on the Studio A property. But that initiative began to change after a grassroots campaign to save the studio was orchestrated by Folds, songwriter-producer Trey Bruce and others. During his concert at Nashville’s Bridgestone Arena in October, even Paul McCartney talked about his experiences in Nashville and said, “You've got to save these old studios, man. History."

Shortly before Christmas, Studio A was finally saved when three preservations completed the $5.6 million purchase of the property from Bravo Development. The plan is to work with Folds for the studio to remain in operation while offering limited access for education and special events.

Those preservationists are Curb Records founder Mike Curb, Nashville real estate and healthcare entrepreneur Chuck Elcan and real estate entrepreneur Aubrey Preston. Preston stepped in to protect Studio A in October after Bravo Development announced its plans.

Not to downplay the importance of Elcan and Preston, but Curb has a lengthy track record in preserving Nashville’s musical heritage. Yes, Curb has had a strained relationship with some of the Curb Records artists -- notably McGraw, who sued to get out of his contract and sign with another label. However, the Mike Curb Family Foundation’s philanthropic efforts include the purchase of historic RCA Studio B in 2002 and subsequently leasing it in perpetuity to the Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum.

In 2005, the foundation acquired and restored the historic Quonset Hut, Columbia Studio A and the Columbia/Sony Building for Belmont University to use for teaching and for hosting events. For his philanthropic efforts alone, everyone in Nashville should be grateful to have Mike Curb as part of the local music community.

Perhaps the bigger question, though, is how do you define history and balance it with commerce?

While some significant artists recorded at RCA Studio A, its heritage isn’t as legendary as the nearby RCA Studio B, which opened in 1957 and still stands. A short list of hits recorded at Studio B include Eddy Arnold’s "Make the World Go Away," Bobby Bare’s "Detroit City," Skeeter Davis’ "The End of the World," Charley Pride’s "Kiss an Angel Good Morning," Porter Wagoner’s "Green, Green Grass of Home," Elvis Presley’s “Little Sister,” Waylon Jennings’ "Only Daddy That'll Walk the Line" and John Hartford’s “Gentle on My Mind.” Beyond that, it was the studio where the Everly Brothers recorded "All I Have to Do Is Dream," "Cathy's Clown" and "('Til) I Kissed You,” Roy Orbison recorded "Running Scared," "Crying" and "Only the Lonely (Know How I Feel)" and Dolly Parton recorded "Jolene," "Coat of Many Colors" and "I Will Always Love You."

And while Curb’s generosity has led to the restoration and renovation of the Quonset Hut, the studio where Patsy Cline, Johnny Cash, Brenda Lee, the Byrds, Simon & Garfunkel and countless others recorded, the original studio area was dismantled in 1982 when Columbia Records needed additional space for its art department.

The truth is that Nashville has generally done a poor job when it comes to preserving its historic buildings. Long gone is the Tulane Hotel, where three engineers from WSM-AM opened Castle Studio, the city’s first recording studio. Much more recently, the building that housed RCA Victor’s first permanent studio in Nashville was demolished to provide additional parking spaces for an automobile dealership. Among the records made there were Presley’s “Heartbreak Hotel.” However, that studio, too, was divided into a control room, audio booths and editing suites after Jim Owens Productions leased the building in 1983 for the production of TV shows such as Crook & Chase. There are plenty of other examples involving the demolition of historic buildings in the downtown area which have no strong country music connection.

In terms of country music history, the biggest survivor is Ryman Auditorium, longtime home to the Grand Ole Opry and one of the greatest concert venues in the world. After the radio show moved to the Grand Ole Opry House at the Opryland theme park in 1974, the Ryman fell into disrepair and was seldom used as a performance venue because it failed to meet fire codes.

Had the resurgence of downtown Nashville along Broadway and Second Avenue been as vibrant as it is now, I’m sure a developer would look at the Ryman lot as a prime location for another hotel. Fortunately, Gaylord Entertainment, which owns the Opry and the Ryman, had the decency to renovate the building and reopen it in 1994. It remains a jewel even after it was overshadowed by the SunTrust Plaza office building that was completed in 2007.

At the moment, Nashville is going through a major growth spurt. More and more people are moving to town, and more and more apartments and condos seem to be rising on nearly every block. I’m not an urban planner, a real estate tycoon or a financial analyst, and I’m certainly not smart enough to offer any solid answers about what needs to be preserved for history and what qualifies for urban renewal.

However, you have to wonder what’s going to happen to Music Row and whether it’s going to turn into just another generic neighborhood you might find in any other city. Is this inevitable? And does it even matter?

Given the national economy, we should probably be thankful for the new residents and new money coming to town. But while we’re being thankful, it makes sense to exercise some caution in making decisions that will be impacting the city for many years to come.