Driver Recalls Hank Williams’ Last Ride (Part 2 of 2)

Jan. 1, 2003 marks the 50th anniversary of Hank Williams’ death. In the second installment of this two-part series, writer Tom Robinson talks to Charles Carr, the college student who drove the Cadillac when Williams died on his way to a concert in Ohio.

The two musicians rose from a brief sleep at mid-morning and searched out the restaurant of the Canton, Ohio hotel. It was New Year’s Day 1953, and they were in town to back an old friend on a new start at a matinee country music show. But first, the hot coffee, ham and eggs.

They had endured a long New Year’s Eve day and night of driving from Nashville through periodic snow, sleet and rain. The weather caused them to arrive too late for the New Year’s Eve show in Charleston, W.Va. But they were in select company, driving with the show’s promoter, A.V. “Bam” Bamford. The show headliner, Hank Williams, never arrived, either. The harsh winter front stalled the singer in Knoxville, Tenn., en route from his trip that began Dec. 30 in Montgomery, Ala.

Even Williams’ attempt at a commercial flight met foul weather and was forced to return to Knoxville. After a brief rest at Knoxville’s Andrew Johnson hotel, the singer-songwriter and his driver returned to the road, steering toward Canton late on this wintry New Year’s Eve in hopes of arriving by show time.

The musicians -- Don Helms and Autry Inman -- eagerly polished off their breakfast before heading to the auditorium to meet with Williams and then play to a packed house. Although rejuvenated, the two were about to be confronted with harsh news that would permanently impact their lives.

About the time Helms and Inman downed breakfast, driver Charles Carr, a college freshman, awakened at the apartment above the Oak Hill, W.Va., funeral home. That he rested at all was nothing short of a miracle. Carr had reason to be tired, having navigated the powder blue Cadillac carrying Williams all through the day and evening of Dec. 31. He rang in 1953 in the wee hours on a highway near Oak Hill when he discovered something terribly wrong.

Dawn had sliced through the dark sky when Carr looked back and noticed the blanket had fallen from his passenger stretched out in the back seat. Carr quietly reached to pull the blanket up. Attempting to move Williams’ arm from across his chest, “I met resistance,” he said. “I knew something was wrong.” Carr stopped at a nearby cut-rate gas station six miles from Oak Hill seeking help, then rushed his passenger to the Oak Hill Hospital. “There were no police escorts or anybody, just me driving him to the hospital,” said Carr. He drove the Cadillac around back where two hospital interns carried the singer in. Soon Williams was pronounced dead. The death certificate cited a heart problem -- “acute right ventricular dilation.” Stunned, yet exhausted, Carr managed to close his eyes in the funeral home apartment and rest.

When Helms and Inman entered the Canton City Auditorium around noon, they were unaware that Williams -- the man called the Hillbilly Shakespeare -- was dead at the young age of 29. “When we got to the auditorium, I saw Bam was serious,” Helms recalled. “He stopped me at the dressing room. If you didn’t know Bam, he was a person who could joke around. But he looked serious and I knew something was wrong. I knew something was wrong before he finished the sentence. He said Hank died.”

The show went on before an audience stunned, like they had lost their next of kin. “Everything about it and that week was strange,” said Helms. “It all seemed abnormal. In Canton, I played those Hank songs, kicking them off like I always did. But someone else was singing ‘em. Then I had to rush back to Nashville and get [wife] Hazel, and then we had to get down to Montgomery for the funeral. ”

Carr had accepted the driving gig while home from Auburn University on Christmas break. His dad ran the limousine and cab company in Montgomery, Williams’ hometown. Williams was in desperate need of a driver to get him to the package shows in Charleston and Canton. Carr didn’t mind. Williams was a family friend, and college students can always use the extra cash. However, Carr could not foresee how this journey would cast him into history while thrusting his passenger into larger-than-life proportion.

For Williams it was to serve as a fresh start from the latest tribulations in a tortured life. With Bamford’s encouragement, Helms was re-teaming with a troubled friend for this engagement. Helms hoped for good things. A cleaned-up Williams and a strong showing in Canton could result in more great things for country music’s great performer.

“I had not seen Hank since the last recording session in September in Nashville,” Helms recalled. “Hank had come up to record. I didn’t know then that would be the last time I’d see Hank alive.” Helms and Williams’ Drifting Cowboys band played with a young Ray Price and other country acts on Opry and concert appearances after Williams left Nashville.

Fifty years later, a reserved Carr -- still living in Montgomery -- is constantly called by media. Journalists seek snatches of history. Carr is the one who can offer personal glimpses of Williams’ final hours. Carr states it best: “I’m not an authority on Hank’s life, but I’m an authority on his death. I was the one there. To think, 50 years later, we’re still talking about Hank is unbelievable.

“Hank was in good spirits when we left Montgomery,” Carr recalled. “It was a dreary day in Montgomery when I picked him up at his mom’s boarding house. When we got to Birmingham that afternoon it was rainy and dreary. We spent the night there. But we had no idea the weather would get so bad. By Knoxville, the rain started turning to sleet or snow.”

What took place between Knoxville and Oak Hill has become folklore. There are stories of painkiller shots and Williams passing away long before the car reached Oak Hill. Carr, who was paid $400 as Williams’ driver, has read and heard all the stories. “We were in Bristol, or it may have been Bluefield, when we stopped for gas,” said Carr. “Hank got out of the car. I said I was going to the diner across the way and was going to get a sandwich and I asked him ‘Do you want one?’ Hank said. ‘No, I’m gonna get back in the car and get some sleep.’

“People do not need to add to Hank Williams’ life,” said Carr. “There were reports of drugs used, but the autopsy said there were no drugs. There were no drugs with us and I never saw him take drugs. If there had been drugs in him, it would have made headlines. All you got to do is see Hank’s autopsy. It shows he had a couple of mild heart attacks. He was given shots in Knoxville, but they were vitamin shots. The hotel doctor gave them to Hank to cure his case of hiccups. He got up after the shots and was all right. When we were leaving the hotel that night, he didn’t feel so good, and I had a bellman bring up a wheelchair and take him to the car.”

Carr also played an important role in Williams’ funeral on Jan. 4, 1953, in Montgomery, as would Helms. “I drove the lead limo with the family,” Carr recalled. “[Ex-wife] Audrey and [Williams’ mother] Mrs. Lillie Stone were in the limo, and Marie Harvell -- Hank’s cousin -- was in there.” Carr said Billie Jean, Williams’ current wife, attended the funeral separately with her father.

Helms and other members of the Drifting Cowboys backed the Opry stars that journeyed from Nashville to perform at the service. Roy Acuff, Ernest Tubb, Red Foley, Webb Pierce, Carl Smith and Jimmy Dickens … all were there along with Fred Rose, Williams’ publisher and lyrical editor. The emotional farewell played out at the City Auditorium where a reported 25,000 onlookers poured onto the street and sidewalk. Williams was the hillbilly mega giant -- and the large Montgomery gathering was certainly one reserved for royalty.

Helms recalled the emotional task of playing his double-neck steel guitar on the stage while peering a few feet below into the open casket of his departed friend. “That was tough,” Helms said, shaking his head. “It was sad. I’d play and look down and see him there. Put yourself in that position. Your best friend is down there. We played ‘I Saw the Light’ and everybody sang. It was very touching. We all got through it.”

A couple of days after the funeral Carr returned to Auburn University. Occasionally a student would ask if he was the same Charles Carr driving Williams when he died. It was a slice of fame he really didn’t wish to have. Half a century later, and in his late 60s, fame has been rekindled. Through the years Carr has owned different businesses and is currently a real estate agent. And through the years, Montgomery has remained home.

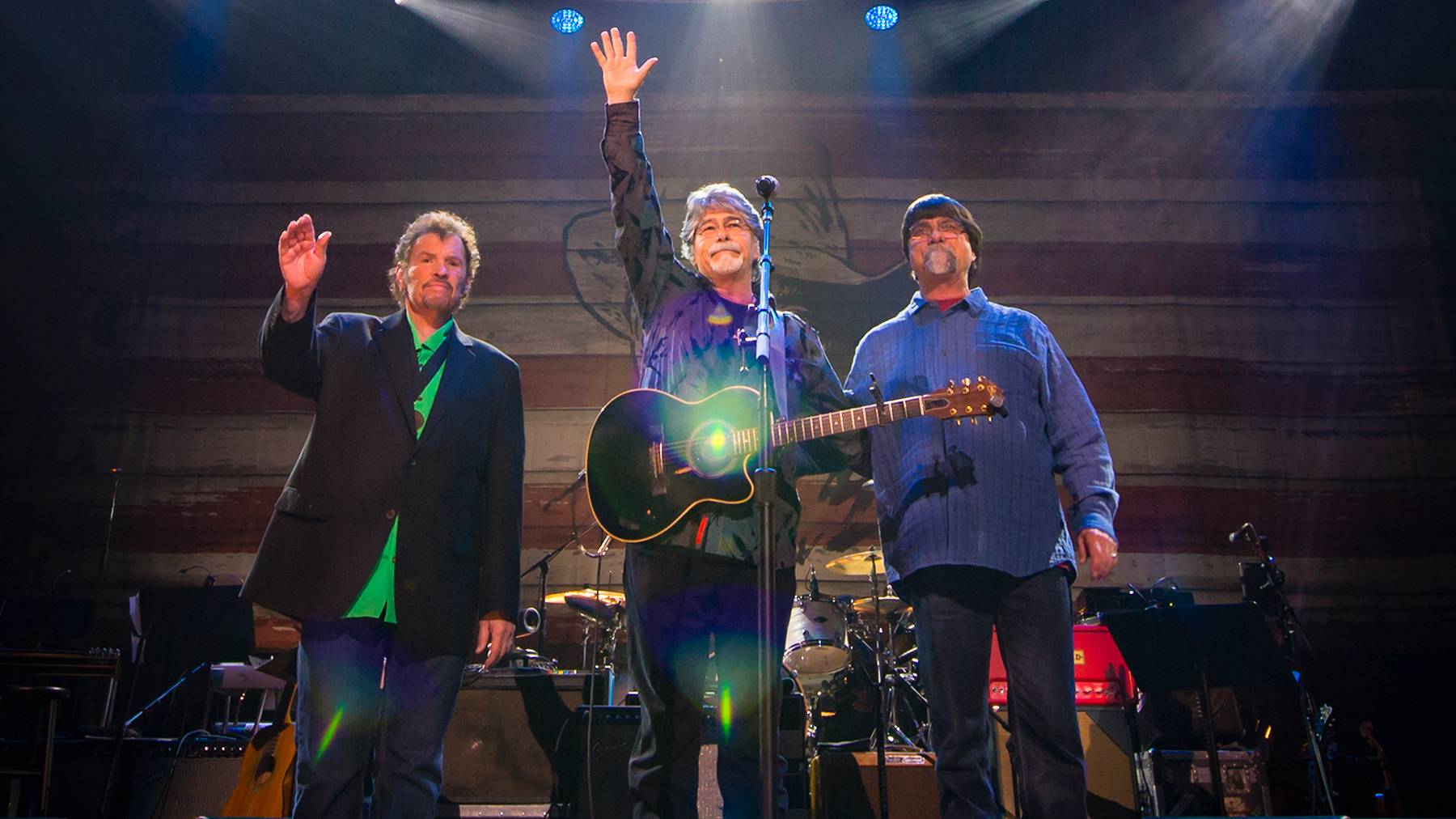

Helms, who resides north of Nashville with wife Hazel, carries on the Williams legacy. He played many years with Hank Williams Jr. Now in his mid-70s, Helms plays for Williams’ daughter Jett Williams. “I’ve played for the Williams family,” Helms said proudly. “Every day I’m touched by Hank. He’s on my wall, he’s on my record player and he’s in my heart.”

In 2002 Helms performed with the Nashville Symphony, at the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame and the New Orleans Jazz and Heritage Festival. And what does Helms play in the crowd of sophisticates or rockers?

“Why, I play Hank,” he grinned. “That’s what they want to hear from me. They still want Hank.”

Read part one of the the two part series -- Hank Williams: Songwriting Legacy Lives (Part 1 of 2)