Kenny Rogers, Bobby Bare, Jack Clement Inducted Into Country Music Hall of Fame

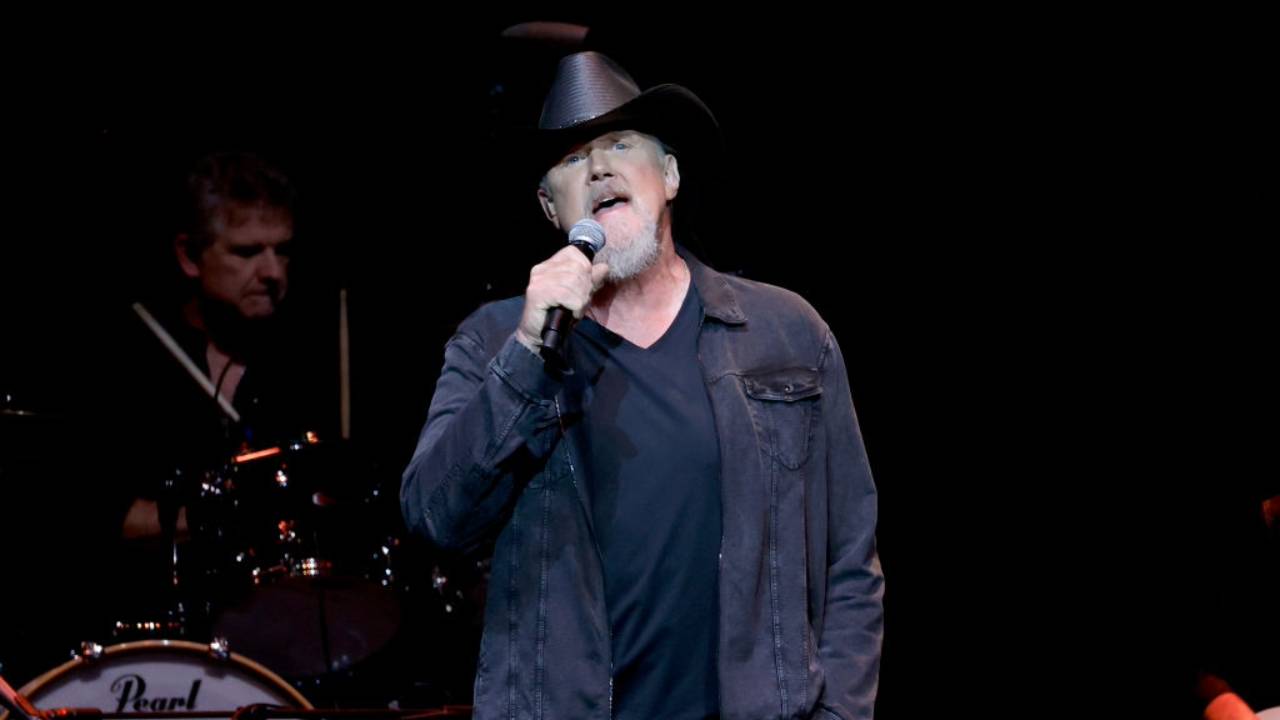

Kenny Rogers, Bobby Bare and the late Cowboy Jack Clement were officially inducted into the Country Music Hall of Fame during a Sunday evening (Oct. 27) medallion ceremony that once again proved to be the best country show in Nashville.

Providing the musical highlights were Connie Smith, John Prine, Kris Kristofferson, Marty Stuart & His Fabulous Superlatives, Emmylou Harris, Rodney Crowell, Buddy Miller, John Anderson, Darius Rucker, Don Schlitz, Barry Gibb, Kelly Lang, Alison Krauss and the Medallion All-Star Band.

The approximately 550 invited guests who witnessed the proceedings were seated in the recently-opened CMA Theater, a state-of-the-art auditorium capable of holding 800.

The medallion ceremony -- so called because of the engraved medallions presented the honorees -- was a warm amalgam of live performances and nostalgic reminiscences about the honorees' circuitous paths to stardom.

Rogers, who grew up poor, related how he broke into show business at the age of 4 by serenading nurses in a nearby nursing home. Bare recalled sleeping in a friend's bathtub during his leaner days. Clement's friends remembered him as a man who excelled at virtually everything he set his hand to -- and having great fun doing it.

Adhering to the ceremony's tradition, the festivities began with the playing of a historic record from the Hall of Fame's Bob Pinson Collection. This time it was Bing Crosby and the Andrews Sisters' 1943 country and pop hit, "Pistol Packin' Mama."

Connie Smith, who was inducted into the Hall of Fame last year, followed with a rousing rendition of the Hank Williams gospel tune, "When I Get to Glory (Sing, Sing, Sing)."

Kyle Young, director of the Hall of Fame and master of ceremonies, recognized Hall of Fame members in the audience and called for a moment of silence to honor the three Hall of Famers who died within the past year -- George Jones, Gordon Stoker (of the Jordanaires) and former record executive Jim Foglesong.

To start the first segment, which was devoted to lionizing Clement, two trumpet players came out and played the intro to "Ring of Fire," the hit Clement arranged and produced for Johnny Cash.

Young described Clement's colorful career arc, including serving in the Marines, working as a dance instructor, playing in bluegrass bands, producing and engineering for the fabled Sun Records in his hometown of Memphis, Tenn., breaking through as a songwriter, forming a publishing company, establishing his own record label, championing and producing Charley Pride and presiding over an artists' salon at his home in Nashville that he dubbed the Cowboy Arms Hotel & Recording Spa.

John Prine, who said he counted Clement among his pivotal influences, sang "Ballad of a Teenage Queen," which Clement wrote and Johnny Cash had a No. 1 on in 1958.

Kris Kristofferson came next with "Big River," another 1958 Cash hit Clement produced.

Stuart and his band delivered "I Know One," a Clement composition that helped launch Pride's career. Stuart said when he first met Clement, the maestro was dancing around the room with a martini on his head and never missing a step.

Then Emmylou Harris, backed by Buddy Miller and Rodney Crowell on guitars, wrapped up the musical tribute with "When I Dream," a Sandy Theoret song Clement recorded and charted in 1978.

Pride came to the stage to induct Clement officially and introduce Clement's daughter, Allison Clement-Bolton.

She mused about the many ways her father might have thanked the crowd for being there to honor him.

"How do you present the man with a thousand personas?" she asked.

She imagined her father talking to her from Alpha Centauri, a celestial locale he alluded to in his 1978 chart single, "We Must Believe," written by his friends Bob McDill and Allen Reynolds.

"He was blessed with the belief that what he did should be fun and pleasing," Clement-Bolton said before concluding her remarks by quoting her father's admonition, "if you're not having fun, you're not doing your job."

Clement died Aug. 8 at the age of 82.

To introduce Bare's part of the program, the band played the opening notes of the singer's signature hit, "Detroit City."

Young noted that Bare was raised on a farm in southern Ohio during the Great Depression and saw his family fragmented after his mother died. After some small show business success in his home state, Bare migrated to Los Angeles, where he met future songwriting great Harlan Howard, guitar whiz Speedy West and singer-songwriter Wynn Stewart.

He first tasted fame as a pop artist in 1958 when "The All American Boy," a song he had co-written and recorded as a demo, became a No. 2 pop hit. Unfortunately for him, it was released under the name of his co-writer, Bill Parsons. Afterward, Bare again turned his sights on country music.

Through the intervention of Bare's friends in California, Chet Atkins signed him to RCA Records in 1962, thereby giving him a base for an eight-year string of hits that included "Detroit City," "500 Miles Away From Home," "Miller's Cave" (a Jack Clement composition), "Four Strong Winds," "The Streets of Baltimore" and "Margie's at the Lincoln Park Inn" (which, Young pointed out, was shunned by some radio stations because of its "non-judgmental" treatment of adultery).

Bare was instrumental in establishing the Nashville careers of Waylon Jennings, Billy Joe Shaver and Shel Silverstein, Young continued. During the 1980s, Bare also hosted a popular songwriter series on TNN: The Nashville Network.

Crowell emerged to sing "Detroit City," with Harris contributing harmonies. Miller sang "That's How I Got to Memphis," prefacing his performance by remarking, "There's something about Bobby Bare's voice that I just believe every word he's singing."

Kristofferson then stepped up with "Come Sundown," one of his own songs Bare turned into a Top 10 in 1971.

"He's not just one of the greatest artists," Kristofferson asserted, "he's one of the best human beings I've ever known."

John Anderson belted out "Marie Laveau," which, in 1974, became Bare's first and only No. 1 single.

"Some of the first real country shows I was on, Bobby was the headliner, and he couldn't have been nicer," Anderson told the crowd.

Tom T. Hall, Bare's friend of 50-odd years, took the podium to induct him. The first thing he made clear -- for reasons best known to himself -- was that Bare is allergic to the refrigerant Freon. He recalled the two of them riding through Mississippi one July in a new Cadillac with the windows rolled down and getting stopped "every 20 miles" because "they thought we were drug dealers."

Hall explained his rambling discourse by announcing he has been diagnosed with "PTTS -- post traumatic storyteller's syndrome." (Hall is known as the Storyteller.) He said there was a Latin name for the affliction that roughly translates into "fear of one's own bullshit."

Bare looked approvingly at his plaque after he and Hall unveiled it.

"I really like that," he said. "It's about 10 times better than I expected."

In prepared remarks, he first thanked his sister, Delma, who "has taken care of me since I was 5 years old when our mother died. [She] has been my rock, my counselor, my ATM, my one place to be always."

Among the others to whom he expressed gratitude were Speedy West ("the first important person to believe in me"), Harlan and Jan Howard ("they let me stay at their house, fed me and let me sleep in their bathtub"), Chet Atkins ("I wouldn't be here without Chet the Greatest") and Shel Silverstein ("the most brilliant, creative person I ever met").

"The gods have always smiled on me," he declared. "I'm just a singer -- and ain't I something!"

The crowd loved that and gave him a standing ovation.

Young returned to the stage to summarize Rogers' musical achievements. He characterized it as "a life of vigorous and diverse creativity" that, apart from music, also embraces writing, acting, photography and philanthropy.

Rogers was raised in government housing in one of the most impoverished sections of Houston. But he came from a musical family and was quick to carry on the tradition. He began to flower musically in high school with a vocal group called the Scholars. His first single as a solo artist came in 1958 with "That Crazy Feeling." It earned him an appearance on American Bandstand.

Later he played bass in the Bobby Doyle Three jazz band. Then during the folk music revival of the 1960s, he joined the New Christy Minstrels, after which he helped form the First Edition. It was with the latter group that he scored his first national hit, "Just Dropped In (To See What Condition My Condition Was In").

But it was with the renamed Kenny Rogers & the First Edition that he sensed the power of country music via their hit recording of Mel Tillis' "Ruby, Don't Take Your Love to Town."

Opting again to go solo, Rogers shook the country music timbers in 1977 with the mournful story song, "Lucille." It became his first No. 1 country single and even reached No. 5 on the pop chart. It was the beginning of a long period during which his songs, such as "The Gambler," "She Believes in Me," "You Decorated My Life," "Coward of the County" and "Lady," charted high in both formats.

Young noted that Rogers, who is now 75, recently signed a long-term recording contract with Warner Bros.

To sample the Rogers canon, Darius Rucker sang "Lucille" -- and was interrupted by applause after the second line.

Don Schlitz ambled out to perform "The Gambler," which he wrote and released as a single on Capitol Records in 1978, just a few months before Rogers made the song his own.

Schlitz joked that he has been forced to play the song with different chords -- just so people won't think him "the worst karaoke singer ever."

"Tonight," he said, looking directly at Rogers, "I'm happy to sing it the right way -- your way."

Bee Gees member Barry Gibb and Kelly Lang took center stage to sing "Islands in the Stream," the Rogers-Dolly Parton hit from 1983, which Gibb co-wrote with his brothers, Maurice and Robin.

"My friends know how much I love Kenny, and they send me pictures of him on the phone," Alison Krauss said with a smile when she came out to sing "Sweet Music Man," Rogers' own composition and a Top 10 hit for him in 1977.

She said when her young son was shopping for a Christmas present for her he knew exactly what to buy -- an album of Kenny Rogers love songs.

In summarizing Rogers' impact, Young said, "He belongs to an elite group of American artists whose music holds such universal appeal that they have become household names around the world. He has sustained his career for six decades. Tonight he becomes a headliner for all eternity."

Young called Garth Brooks to the stage to induct Rogers. Brooks, who joined the Hall of Fame last year, made it clear immediately that there was something wrong with that sequence of events.

"In this business," he intoned, "anyone who comes before you is a god. Anyone who comes after you is a punk. This is so backward."

He said Rogers was the first to give him an opening slot on a tour. That enabled him to build his own audiences, particularly in the hard-to-crack Northeast. It also showed him how the big guys travel and are treated. "When you show up with Kenny Rogers," he said, "the red carpet rolls out."

He praised Rogers as the consummate entertainer.

"I was smart enough myself to watch him every night," he said. "If you want to know how to treat people, Kenny Rogers will show you."

Rogers began his acceptance remarks by noting that his induction "is the pinnacle of all my successes."

Looking back to the start of it all, he said he began his career by singing "You Are My Sunshine" in a nearby nursing home when he was 4. For this performance he would get a quarter. That taught him never to sing without getting paid for it, he joked.

Although several members of his family were in the audience, Rogers said his one regret was that his mother and father weren't alive to see him honored.

"They would have been so proud," he said.

He recalled winning a talent contest when he was 10 and getting to meet Eddy Arnold, who invited him backstage and let him play his Gibson L-5 guitar.

He praised his brother Leland for believing he had enough talent to succeed.

He thanked Bobby Doyle for introducing him to the music of the 1930s and '40s. When Doyle invited him to join his trio, he at first declined because he couldn't play guitar well enough. But Doyle told him he wanted him to play bass. Rogers said he didn't know how. But Doyle was insistent, sagely observing, "There's more demand for bad bass players than for bad guitar players."

Kirby Stone, founder of the Kirby Stone Four pop group, had some sound advice to offer, too, Rogers recalled.

"He said it's not all wet towels and naked women," he said. "I was so disappointed to learn that."

In a euphoric summation of how he felt, Rogers exclaimed, "The Hall of Fame is forever, baby."

Among the other Hall of Fame members in the audience were Brenda Lee, Ralph Emery, Bobby Braddock, Barbara Mandrell, Jimmy Fortune of the Statler Brothers, Sonny James, Harold Bradley, Charlie McCoy, Mel Tillis, Jo Walker-Meador and Bud Wendell.

Following the ceremony, guests gathered for a lavish cocktail party in the Hall's new sixth-floor ballroom.

[flipbook id="1716306"]View photos from the ceremony.[/flipbook]