The Mavericks

Mav-er-ick (mav'-er-ik): an independent; an unbranded calf.

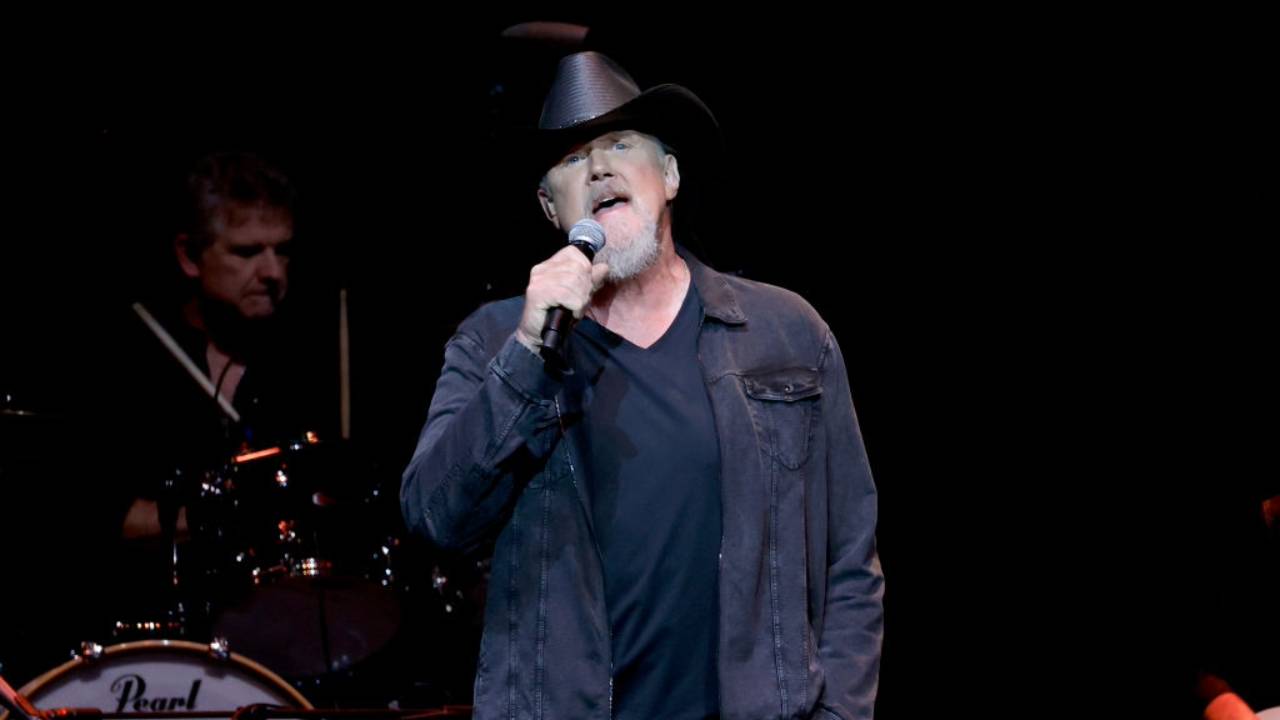

As their name suggests, the Mavericks are a band fond of coloring just a little outside the lines. In many ways they are unbranded, making their own particular type of party music without giving much of a care where it should fit or be played. The colorful four-man band from Miami appeared on the country scene a decade ago, and the genre has never quite been the same since. Sometimes irreverent, always outspoken, Raul Malo, Paul Deakin, Robert Reynolds and Nick Kane are in many ways the epitome of everything that is both good and challenging about that four-letter word, B-A-N-D. And with the release of their latest album, Super Colossal Smash Hits of the '90s, they stand poised and ready to tackle another decade of making great country music and stirring things up in a way only the Mavs can.

In the tradition of many great rock and even country bands, the Mavericks have caused their share of controversy over their decade-long history. But amidst the equipment failure tantrums, the offhand (and sometimes less-than-tactful) remarks -- often meant in jest -- and the nagging rumors that beset a group filled with colorful and creative characters, there remains one constant: great music. After 10 years, four million records sold and a slew of awards from their peers, the Mavericks still enjoy the same thing -- making and playing great music. Whether it's for a crowd of 1,000 at Buck Owens' Crystal Palace or 150,000 at England's Prince's Trust Concert, they get the same kick out of performing now that they did when they first left Miami 10 long years ago for Music Row and the big time. Compiling a best-of record brought back lots of memories for the band, reminding them of just how far they've come on their journey through the '90s.

"Listening to this record was an interesting experience," admits bassist Reynolds, who is dealing with a breakup with wife Trisha Yearwood while promoting the new record. "It was a little like taking a photo album and flipping through the pages. Or a scrapbook -- you're leafing through the pages and occasionally a smile crosses your face or you get a little pang in the heart. I had a feeling for place and time for a lot of it, where we were in our careers during certain hits, what it felt like to head out on the road when we were only in a van, all the ups and downs ... and it gave me an emotional ride. And it was good!"

"The first thing I felt was OLD!" kids Mavericks drummer Deakin, laughing. "But listening to those songs makes me think about the changes we've gone through, and especially makes me remember the raw energy and our need to make music back when we started out. We still have fun now, but back then, we were eating, sleeping and breathing the music! We did it for fun, but it was so much fun in those days that we probably got a little obsessive about it almost!"

Now three of the four have families that require a good bit of that energy, and the music has taken its rightful place in the balance of their lives. Not that they've mellowed out THAT much, mind you. The boys can still rock the house, as evidenced by one listen to Super Colossal. From the opening strains of "Things I Cannot Change" (a new pop-sounding tune co-penned by adopted Maverick Jamie Hanna), to their huge UK smash, "Dance the Night Away," the Grammy-winning "Here Comes the Rain" and the fun-spirited anthem "All You Ever Do Is Bring Me Down," the record takes listeners for a dance down memory lane, with a few new stops along the way. In true Mavericks' style, it is 100 percent pure fun, start to finish. But the road to the studio to create their fifth album, their first on Mercury/Nashville, wasn't exactly smooth.

"There was a really tumultuous time between 1994 and 1996, when we had created the What a Crying Shame album and were selling lots of records and touring constantly and winning awards, and we were about to implode because we were so fatigued and the travel was killing us," remembers Reynolds. "We decided to take a year off, and that year off is perhaps the reason we're having this conversation now. Because without it, it's possible the Mavericks wouldn't have made 10 years. Not that we were necessarily talking about breaking up outright, but we just needed that time away. It was completely necessary for us. I'd really like to see more of Nashville take rock 'n' roll career patterns and do like REM and Tom Petty and Bruce Springsteen. Just work your ass off, like you've never done before, but when you're done, hang it up for awhile and retreat from the business."

After their self-prescribed sabbatical, the band returned to the country scene with renewed vigor in 1998 and recorded Trampoline, a record full of brass and horns that was loved by critics but seemed to confuse the hell out of country radio. "There was definitely a point where we contemplated calling it quits cause we were so burnt out and didn't know from that perspective whether we had anything creative to do together anymore," echoes Deakin. "So it was a nice surprise that when we took the time off, we were able to come back and make a record like Trampoline."

Though it never took off in the States, a single from the album, "Dance the Night Away," became a runaway smash in the UK, propelling that album to triple platinum status there. Instead of worrying about not being let into the game here, the Mavericks simply took the ball and ran with it overseas, parlaying the situation into international success.

"People think our career has gone down since Trampoline, but that album has sold more than Music for all Occasions," explains Deakin. "It's almost platinum worldwide. It was definitely a departure for us and was not the most country record we've made. We made that record for ourselves in a way, but we always do. That one was no different."

"We were validated wildly by the UK success," admits Reynolds. "We recorded Trampoline with a great deal of confidence, and although we had to be honest about the fact that we were departing from mainstream country with it, we were optimistic about something positive happening with it in the States. But I think at one point, the label's perspective and radio's attitude about dealing with the Mavericks on our terms because we were often outspoken, and all those things kind of converged. And we were kind of shut out a bit. But we didn't lose sight of our goals, or think we lost our purpose or relevance in all of this. And we still haven't.

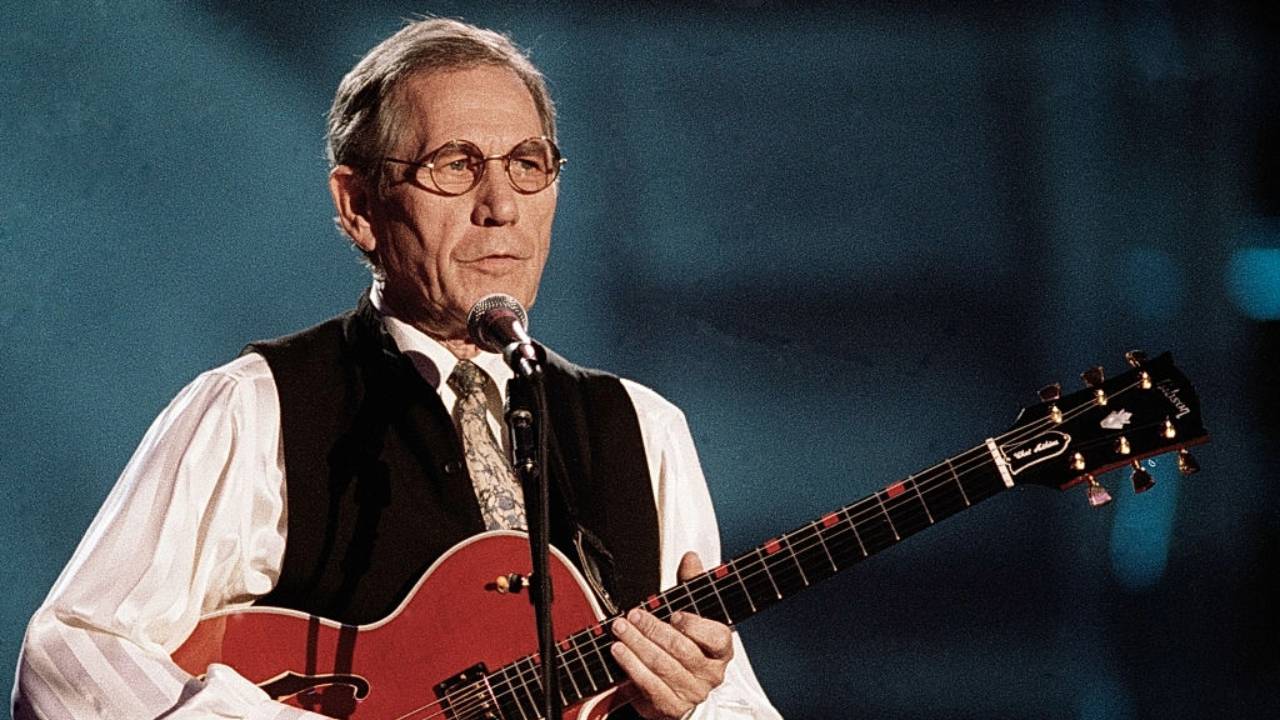

"There are lots of people in this country who aren't worried about genre but love great music. Bonnie Raitt, Muddy Waters, the Stones, Nat King Cole ... if they dig it, they buy it, and listen to it. And all that music is specific and special to certain moods that person might have. That's what we feel like we're about. We're a pleasure band -- we go for the pleasure zones to make people happy. And there are a lot of people in this country who are as open-minded musically as anyone we've encountered in the world. They're the people who come to see us play concerts and watch us on TV; they're the people who hire us in the industry to play the Johnny Cash special; they are the Emmylou Harrises who ask us to be on the Gram Parsons tribute album. That's who we make our music for."

And once again, the Mavericks are out there making their brand of music for all who'll listen and join in the party. The new record is out, and in Mavericks' grand fashion, the band rang in the new millennium by playing the biggest New Year's celebration in the UK in Scotland. As they gear up for another decade together and prepare to create some more great music, they are proud of the fact that they are, in fact, still a creatively-driven, working band. "Ten years is a long time in a relationship of this nature," says Reynolds. "When you get to that mark, that in itself is an award. There should be an award presentation for anyone who can just hang out that long together! 'Saltiest Old Band Award,' that's what they'd call it! They'd name it after the Stones. And maybe we'd get one. Because as long as we have something that makes us valid, we'll keep making records. But when that validity is gone, that purpose, then you have to go away."